We know it’s only a matter of time before Dodge drops its next turbocharged Challenger or Charger muscle car now that the Hurricane I-6 is out. Even so, Stellantis engineers are already looking at ways to affix the turbo to the head as engine bays get more and more cramped. While some manufacturers have gone the route of the “hot Vee” and Stellantis themselves have eliminated the exhaust manifold from their turbocharged engines, the engineers are looking to radically change how the turbo is attached to the cylinder head.

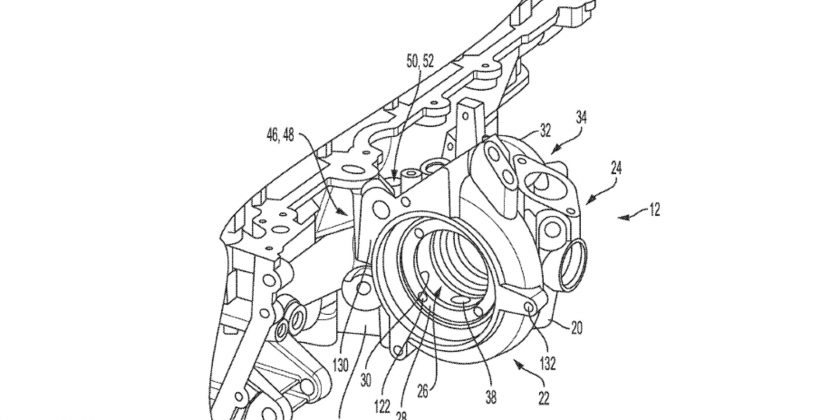

That radical change comes from a U.S. Patent filing earlier this month, in which it describes how to integrate the entire turbocharger housing into the unit’s cylinder head. We’re not talking about just integrating a manifold or even the turbine side of the housing, but the full turbocharger housing including the compressor.

The idea is that this casting would have provisions for automated arms to grab onto and the cartridge would also have guide pins with matching bores to line it up with the integrated housing before being bolted in. From there, a compressor housing cover would be attached to the integrated housing, sealing the compressor side and forming the aperture where the compressed air would scroll through before heading to an intercooler or straight into the intake. The wastegate is also integrated into the head casting, reducing parts further by not requiring new heat shields.

Why Integrate the Turbo Into the Cylinder Head?

There are several advantages that the patent lays out on the reasoning for this radical integration of turbo and head. The most obvious part is reduction in parts, as you remove the manifold and cast the turbo straight into the head, you lose the need for some many gaskets, additional fasteners, and some of the complexity during engine assembly at its plant. This could also make servicing a bit easier, as well, as you’ll be able to replace a full cartridge without tearing the turbo off the manifold and then take it further apart. You would just unbolt the front cover, unbolt the cartridge, and replace that portion of the assembly.

The other advantage of this patent is that it makes the turbo and head package that much more compact. By completely eliminating the manifold, you reduce the space between the turbo and the head that much further. Again, it would allow for improved service for your technician as the room around the turbo would increase, save for the space between the turbo and head. Another advantage is one that we’ve seen by removing the exhaust manifold and hooking the turbocharger straight to the head, as is done on the Hurricane I-6 engines. You’re removing another heatsink between the exhaust and the catalytic converter and that allows for quicker light off of the converter for emissions.

Then there is something you’ve probably not thought of: noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH). While you won’t see things that are bolted together moving (provided the assemblies are fastened correctly), anything that is bolted on creates microscopic movements. The more you need to fasten together, the more those movements add up and increase noises and vibrations within certain frequencies. Then there is the integration of the wastegate, which also removes noises related to the resonance created when it opens and closes, the noises of the airflow from the manifold (that’s no longer there) to the turbocharger and wastegate, and some whine from the rotor group where some unbalance can occur.

The final advantage to mention is the cost in both the reduction of parts but also the speed of installation time, but the patent doesn’t really mention how integrating the turbo housing to the head does that. We would point out that there would be additional costs in the casting, and not just because of it being a new casting. In order to get some of the turbocharger’s internal features into this integrated form, use of investment casting would be required.

How Would You Even Cast This “TurboHead?”

If you’re unfamiliar, this is a casting process that forms a temporary mold. In this specific case, a temporary mold would be placed between the mold of the main casting for the internal features of this integrated turbocharger. This internal mold would then be broken apart or melted (depending on how the internal mold was created) before finish machining is performed.

This means that you wouldn’t just need a mold for the main casting, but an additional mold plus material to create the investment cast. The good news is that investment cast mold material can be reused after breaking it down again, so there is a reduction of some costs after the initial run, but that doesn’t account for the additional labor and time to remove it. The only other way is to use 3D printing, which it seems the patent does leave open to interpretation by saying, “In order to reduce or prevent such issues in the present disclosure, the turbocharger housing is integrated (e.g., cast) into an aluminum cylinder head…”

Unfortunately, 3d metal printing hasn’t quite reached this level of production. While parts by enthusiasts and small companies work for a small or individual scale of production, the speed and precision required for mass production is still a ways out for this form of creating parts.

Again, as with any patent, this doesn’t point to any immediate production of anything. It is an idea that has been put to paper and potentially into a single part to demonstrate an example of said idea. While all Stellantis brands are going to be fully electric at some point in the near future, the vehicles that will continue to use ICE and need as much engine bay room as possible will see a great benefit from this patent coming to production fruition.

Source: Read Full Article