Should you buy a plug-in car? This is a tough question with no simple answer, but as things stand in early 2021, our general response is this: If you want to make a difference, the answer is yes. If you want to save money, the answer might be no, but that depends a lot on how much electricity and gasoline each cost where you live, as well as what type of conventional car you might buy instead of an EV.

Related: Which 2020 Electric Cars Have the Greatest Range?

From the environmental perspective, there’s no question electric propulsion is superior despite propaganda to the contrary. This is why plug-in vehicles and regular hybrids have sold in the U.S. at all. Why they haven’t done better is because this is the land of consistently cheap gasoline and diesel fuel, and until efficient and/or clean alternatives are priced to beat the status quo soundly (either naturally or through incentives), they won’t make up a major chunk of the market. We also await vehicle technology that allows public charging speeds to rival fuel-tank fill-ups before we expect Americans who can’t charge at home to embrace pure EVs.

Just so you know where we’re coming from, Cars.com’s editors are EV believers, though pragmatic ones. We loved driving our 2011 Nissan Leaf and 2011 Chevrolet Volt, as we have many other plug-in models since then. But they have their limitations, and it’s not just the obvious one, range.

Below, I’ll attempt to answer the basic questions about two main types of plug-in vehicles — pure battery-electric models and plug-in hybrids — as automakers ramp up yet another plug-in push amid questionable demand. The good news this time is that the latest push includes more of what Americans love — SUVs, including more affordable battery-electric SUVs than automakers offered in the past — which are sure to boost sales, at least initially.

What Is an Electric Car?

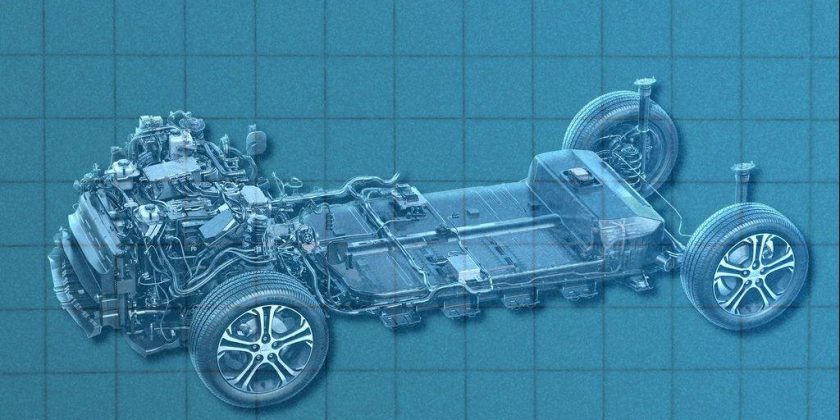

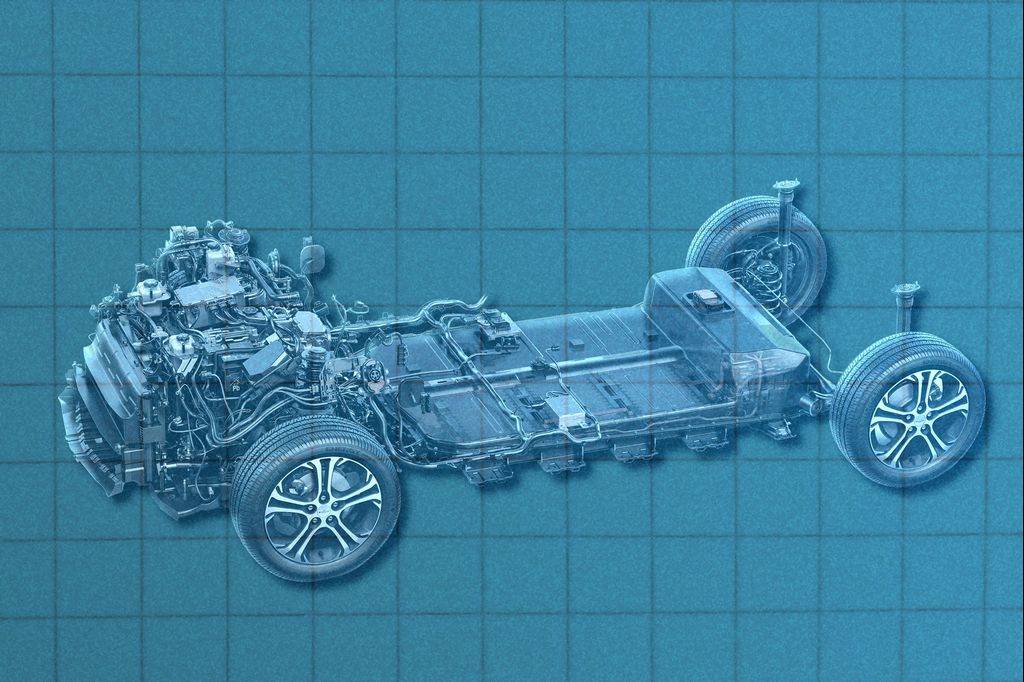

Electricity plays a role in all vehicles, and an important one in common gasoline-electric hybrids, but we’re concentrating here on the vehicles you plug in and drive some distance on electric power alone, which represents two basic types. Typically when people refer to an electric car, they’re talking about a pure battery-electric vehicle that has no gas backup; when it does have a gas backup, it’s called a plug-in hybrid (which I’ll explain next). From the perspective of the automaker, with potential consequence for the consumer, a pure EV could be cheaper to build because it has one drivetrain. But there’s a confounding factor: With no backup propulsion system, more electric range is needed — and that means more battery capacity, which is one of the most expensive components. This can gobble up whatever cost was saved by eliminating the gas engine and everything that goes with it.

What Is a Plug-In Hybrid?

A plug-in hybrid electric vehicle, or PHEV, is a vehicle that can do two things: One, it can drive a limited distance on electricity from a battery that’s been charged by plugging into grid power. Two, it also has a gasoline engine onboard that can turn on to keep the vehicle going so long as you fuel it. The gas backup, whether it drives the wheels directly or provides electricity for the electric motor, eliminates concerns about being stranded with a dead battery, and arguably makes PHEVs a better choice if you or your family own only one car. Pure battery-electric cars, on the other hand, are less ideal if you want to go on long road trips because public charging is slow and unreliable in many parts of the country.

Perhaps the best-known PHEV, and one of the best executions despite its departure from the market after the 2019 model year, is the Chevrolet Volt. But there have also been plug-in versions of the Toyota Prius, now called the Prius Prime, and many others. Frankly, they haven’t been especially popular, and I suspect it’s partly because some of them have had such short electric ranges. Also, some drive better than others, and the inclusion of both a gas tank and a battery pack has often compromised the size (and range) of one or the other — or the cargo or passenger space. Still, there are good ones, such as the Honda Clarity Plug-In Hybrid sedan, Chrysler Pacifica Hybrid minivan and Toyota RAV4 Prime SUV. Many more models are coming, and automakers are working with new platforms designed to accommodate the motors and batteries that once robbed space.

What Don’t I Know About Plug-In Cars?

If you’re new to plug-ins, there are a few things you should know, some of which might surprise you — and are likely to irritate EV evangelists. I’ll address all of these issues below, but they bear calling out:

1. Public charging is not part of the equation; if you’re thinking that’s how you’ll keep your plug-in going, you’d better be a true believer.

2. EVs favor the homeowner. If you rent, or lack a garage, a pure EV is probably out of the question.

3. Range goes to hell as temperatures fall, losing more than 40% at 20 degrees, according to AAA (and quite obvious to anyone with EV experience). There’s a reason plug-ins are more popular in warmer climates.

4. Charging takes a long time, which is just one reason behind our claim in No. 1 above.

5. Federal incentives worth as much as $7,500 on plug-in models with sufficient battery size have been tax credits, not cash rebates, since their inception. Funds won’t come back to you until tax return time for the year of purchase, and the amount depends on your tax liability (income level). In other words, you’ll wait months, at minimum, and might not get the full amount. Notably, as of the start of 2021, GM and Tesla vehicles have expended their allotment and aren’t eligible for these incentives, though President Joe Biden’s administration might revise this program or institute others. (Note that some or all of these incentives can be calculated into the leases of eligible models starting with the first payment, which makes them pretty attractive — but as a result, there’s no lump incentive payment to a consumer who leases.)

How Much Range Do I Need?

Our short answer: not as much as you probably think, though many disclaimers bear mention. Once you accept that EV ownership is fundamentally different, your true needs become clearer. If you accept my other positions — primarily that the point is to charge at home overnight and not rely on public charging — you’ll recognize that it’s all about how far you drive on a daily basis, not how far you drive between stops at a filling station. Our first EV was a 2011 Nissan Leaf with an estimated range of 72 miles, which plummeted in a Chicago winter. You know what? It was plenty when we charged at both home and work, and it proved to be plenty even when we charged only at home, despite the effect of cold weather on our range. Pure EVs with modest ranges would make great commuter cars for most Americans. The requirement that the same car be able to drive much longer distances is what makes an EV less affordable and less likely to recoup your investment. The 2021 Nissan Leaf starts at $32,620 with an EPA-estimated range of 149 miles. The Leaf S Plus, with its larger battery and 226 miles, costs $39,220, a whopping $6,600 to add 77 miles of range (see the two side by side; prices include destination).

If you’re considering a plug-in hybrid, it’s the same equation. Technically, if you have a 20-mile commute and do 18 miles of it on electric power before the gas kicks in, that’s great (and usually cheaper than gas alone would be), but it’s even better if you’re running electric all the time. The length of your commute, electric range of the PHEV and how many opportunities you have to charge will all come into play.

How Long Does EV Charging Take?

The short answer is “too long.” The slightly more detailed answer is “too long, and there’s no simple answer because variables abound.” Having said that, if you’re doing it the right way, which is charging your EV at home overnight, charging typically turns out not to be the problem people think it is, and plugging and unplugging once a day proves preferable to visiting a gas station as often as we’re accustomed to. But we’re not going to say charging speeds are a high point of plug-in vehicles. They are one of the reasons public charging isn’t the solution that uninitiated shoppers often expect.

We’re all accustomed to spending five minutes at a gas pump to add several hundred miles of range, and unfortunately that’s the standard consumers expect. (If this is to become a reality for EVs through solid-state batteries or some other innovation, it won’t come soon, or cheap.) The ugly truth is that charging on a regular 120-volt household outlet adds only about 5 miles of range for every hour of charging at best — for an efficient, small plug-in car. Something like 3 miles per hour is more likely with an SUV. For a plug-in-hybrid car, as opposed to an SUV or van, 120 volts can work fine, and you won’t have to spend extra money on a 240-volt circuit if you don’t already have one (though 240 volts is better for preconditioning the cabin — running the heat or air conditioning before you depart so you don’t waste as much battery and, thus, range).

Home charging at 240 volts, which is called Level 2, can add 10, 20 or even more miles of range in an hour’s time if it provides enough current and the car itself accepts it (the vehicle is one of many potential choke points).

Unfortunately, low or high temperatures can slow the charging process, as can the state of battery charge. Rechargeable batteries charge fastest when empty and slowest when nearing full capacity.

What About Public Charging?

Public charging is nice if you can find it, but don’t buy an EV expecting to rely on it. I’m sure there are people who buy EVs and manage to get by on public charging because everyone’s needs, expectations and environments are different. And we know that Volkswagen is making DC fast charging free at Electrify America stations for three years with the purchase of its 2021 ID.4, while Hyundai is offering roughly 1,000 miles’ worth of free charging over the same network for all-electric versions of the Ioniq and Kona. Owners are sure to exploit both. But at this point, our position remains that if you can’t charge at home, there’s no point to buying a plug-in. Charging takes a long time (see above), and public charging typically costs more than home — especially Level 3 DC fast charging (Supercharging is Tesla’s term), which is faster than Level 2 but still doesn’t match the gas-pump expectation. Most public charging is Level 2, and it’s sometimes free; it’s also sometimes in use when you need it, or it splits the power between two attached vehicles (which slows the charging rate), or it’s broken when you need it.

There may be free charging options now, but are you willing to invest in a vehicle that relies on someone else providing the juice? After we bought our Leaf and Volt, we went from being the only ones using the two free charging points that appeared in our parking structure to being consistently beaten to them by other EVs that hogged the chargers all day. After a couple years, the parking lot began to bill after four hours’ charging time, which dampened the appeal yet made little difference in availability. Eventually these units stopped working and then were removed entirely, leaving us in a charging desert many blocks away from an alternative. The above situation transpired over the course of roughly five years. Other regions are better, but this illustrates how much the EV owner is at the mercy of external forces.

Is Home Charging Expensive?

In one regard, home charging isn’t expensive. Your electric bill will go up, but usually not as much as your gasoline bill goes down, especially if your old car used premium fuel. Where more expense might come in is with the installation of 240-volt Level 2 charging. Like most aspects of plug-ins, there’s no simple answer to the question of cost.

Level 2 charging hardware ranges from about $200 to $1,000 and higher current capacity costing more, though it seems automakers are increasingly following Tesla’s lead and including portable Level 2 charging cords with their vehicles instead of types limited to 120 volts. Installation costs are the big mystery, depending on how close your garage or parking space is to your home’s electric service panel. If you already have an unused 240-volt circuit in your garage, you might be ready (or very close to ready) to being able to charge at home. If your service panel is in the garage, you might be less than $100 away from being in business. But if a new 240-volt circuit must be run to the parking area, it could mean several hundred to several thousand dollars’ worth of installation charges. It all depends on the distance involved and what’s in between — walls, concrete, asphalt or what have you. This is why the process of buying a plug-in usually starts with a site survey from a licensed installer or electrician.

More From Cars.com:

- 2021 Ford Mustang Mach-E Review: Good Numbers, Harsh Ride

- 2021 Polestar 2 Review: Is This the Future of Sports Sedans?

- 2021 Chrysler Pacifica Review: Updated Minivan Is a Mega Win for Families

- 2021 Volvo XC90 Recharge Range: Here’s How Far We Went on Electricity Alone

Will a Plug-In Car Save Me Money?

It’s hard to say definitively because there are so many variables. The cost per mile of a plug-in easily can be less than that of a comparable gas-powered vehicle, and the advantage is even greater if you’re comparing with a car that requires premium gasoline. But bear in mind that electric and gas costs vary widely across the country, so there’s no single verdict. For a rough estimate, the Department of Energy’s eGallon calculator can juxtapose the cost to drive an average EV versus an average gas vehicle in your state, but it’s rough indeed — based on averages of both vehicle types, and based only on regular gas. If you’re one to dig deeper, find your average price per kilowatt hour and compare it to the local cost for the particular grade of gasoline you’d use.

In our experience in Chicago, the cost per mile on electric power has been about half that for regular gasoline — and even better versus premium gas. But that’s just the cost of operation. Even after you subtract the incentives available today, plug-in vehicles tend to be relatively expensive. Pure electrics prove to have lower maintenance costs associated with their drivetrains and some other systems, so we see signs of how the car ownership paradigm might shift, but we’re not sure we’re there yet.

Unfortunately, it can shift in the other direction, as well. The federal tax incentives alluded to above already phased out for Chevrolet and Tesla, and the Trump administration expressed interest in eliminating them midstream — once before the tax reforms of 2018 (automakers successfully lobbied to leave them in place) and again shortly thereafter, when GM announced the de-allocation of some assembly plants. The Biden Administration is working on countless initiatives to jump-start EVs, and with its razor-thin majority in the senate, there’s a chance one of them will extend consumer incentives for new EVs and add tax credits for used ones — but then there are the states.

Where some states have additional incentives that tip EVs into the more affordable side of the equation when combined with federal credits, other states haven’t joined in — or they’ve moved backward. Legislators at both the federal and state levels are attempting to institute road usage fees for plug-ins to compensate for the revenue otherwise collected only in gasoline and diesel taxes. (EV advocates claim that the higher prices of plug-ins already compensates in the form of higher sales tax.) Annual registration fees, which also have been equal to or lower than those for conventional vehicles — as an incentive — may also be on the rise. A Consumer Reports study reflects that roughly half of all U.S. states have current or proposed EV fees that it deems “punitive,” or higher than the annual gas tax would be for the average car by 2025. The National Conference of State Legislatures tracks many of these fees.

Is There an Exception?

Perhaps the best chance you have to save money on a plug-in vehicle over the long run is this: Buy a used EV as a second car that you can charge at home. Used battery-electric cars tend to be surprisingly cheap for a few reasons:

- First, they’re used, which alone represents a major discount.

- Second, incentives historically have been available only on new purchases, so the market has subtracted them from the initial value.

- Third, like all cars, EVs keep improving and adding range, so those with shorter ranges seem especially less valuable.

- Fourth, consumers worry about EV batteries dying completely and being prohibitively expensive to replace. In reality, we’ve learned from more than a decade of hybrids as well as plug-ins that outright battery failures are rare. Traction batteries lose about 20% of their capacity over the course of 100,000 miles and/or 10 years, consistently enough that automakers account for it. Warranties are pretty long but don’t cover marginal loss of range. You should worry less about battery failure and more about whether a 20% loss still gives you enough range to work with.

In the above scenario, you have a better shot at coming out ahead with another car available for longer trips and the lower cost per mile of electric motoring based on home charging — even if higher registration fees or road-use taxes come into play. This could be enough to make a believer out of you and reveal how much range you really need should you decide to go electric again. Our experience tells us you will, as do J.D. Power studies that show as many as 82% of EV owners say they’ll definitely consider another one.

There might also be some deals on plug-in hybrids, though it’s tough to gauge. Their market acceptance has been modest at best in the U.S., but automakers are compelled to produce plug-in hybrids to comply with zero-emissions requirements in some states, so there are plenty of new models on the way. There’s a chance, if demand just doesn’t materialize for this type of vehicle, that you’ll be able to get a really good deal on one. Automakers get credit for selling them, not just offering them. Cheap gas, disinterested politicians and widespread climate-change denial are the worst things going for the U.S. plug-in market. The best thing is that many other advanced countries are the opposite in all of these respects, so automakers are building the vehicles regardless.

Cars.com’s Editorial department is your source for automotive news and reviews. In line with Cars.com’s long-standing ethics policy, editors and reviewers don’t accept gifts or free trips from automakers. The Editorial department is independent of Cars.com’s advertising, sales and sponsored content departments.

Source: Read Full Article