If you want to understand why Stirling Moss never won a championship in all his years as a Grand Prix driver, you need look no further than the Portuguese Grand Prix of 1958.

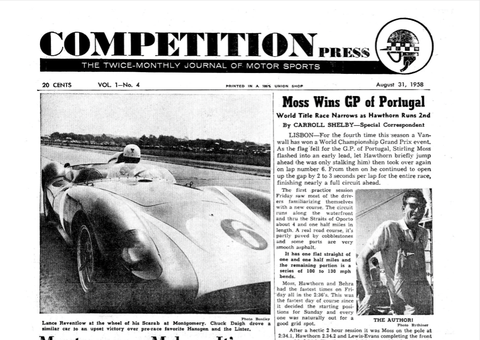

(Digging through the Autoweek/Competition Press archives to get that story, it turns out the race report was written by “special correspondent” Carroll Shelby, who piloted a Maserati 250F in Porto. Ken Miles was listed in the masthead as a “Staff Editor.” Among the Letters to the Editor was one that said, “Congratulations on your excellent paper … I especially like Denise McCluggage’s reporting …” It was signed, “Sincerely, Briggs Cunningham.”)

Moss was on pole for the race in a British-built Vanwall, just ahead of the Ferrari 246 of his rival Mike Hawthorn. The rest of the field included drivers and cars you would pick if you were playing in a fantasy Grand Prix game and were setting up the grid: Jean Behra in a BRM, Wolfgang “Taffy” von Trips in another Ferrari 246, Jack Brabham in a Cooper, Maurice Trintignant and Roy Salvadori in Coopers, Carroll Shelby in his Maserati, of course, Graham Hill in a Lotus and Jo Bonnier in another Maserati 250F.

The circuit itself was, by any modern understanding, a crazy dangerous mess of cobblestones, hay bales and light-rail tracks, the latter which seemed to wind onto and off the course at will. The light rail was electric, so there were power poles scattered throughout the scene “protected” by hay bales. Looking at photos and at a single black-and-white video of the race, any sane person wouldn’t even want to spectate, except perhaps from an airplane, let alone drive or race on it. To make matters worse, when the race started there was a light rain falling on the cobblestones and rail tracks. Imagine how slick that must have been on those hard, skinny tires.

That alone tells you one thing about how brave these guys were back then. “Sunday morning threatened rain and everybody’s face looked like they full knew this would be a very dangerous course if wet,” Shelby wrote. It was wet, at least at first, and it was dangerous. But as they did in that era, everyone just got in their cars and drove. No complaining.

While a few drivers had seen the circuit in sports cars, 1958 was the first year for Grand Prix cars. So the fact that Moss won the pole says a lot about his driving ability.

While there were a few changes in the order early in the race, Moss was in a commanding lead almost the whole way, lapping the field, and won it handily. But afterward there was a protest by race officials against Hawthorn, who had spun up an escape road and stalled on the circuit. When Moss came upon that scene he stopped and waited to see if he could help his countryman. Hawthorn got the Ferrari restarted and finished the race. He had set fastest lap when rejoining the field and finished second, all of which was good for a critical seven points toward that year’s title.

However, “The spin caused protests,” Shelby wrote. “Some claimed he had push-started against traffic …”

Had the protest carried through, Hawthorn would have been disqualified and lost all seven points. When Moss heard about the protest, he immediately came to Hawthorn’s defense, saying that the backing up had taken place off the course on a parallel street. Thus, the matter was dropped and Hawthorn eventually went on to win the season title—by one point.

Can you imagine anything even remotely like that happening today? It simply wouldn’t enter any driver’s mind to defend a rival at their own expense. But Moss did.

He was the last of the gentleman drivers, always out to assure a sporting chance for all, even if it meant losing himself.

As for Shelby’s race?

“Oh yeah! What happened to me in Portugal? Well, seems the last lap when I was ahead of some of the people I’d dreamed of beating for years, a brake locked going down the main straight at 160 mph. I was spun around (?) times on a road 25 ft. wide and only touched one telephone pole, coming to a stop in the center of the road, petrified! That’s racing. —Carroll Shelby”

Source: Read Full Article