Mercedes’ introduction of Dual Axis Steering (DAS) during pre-season testing offered us a glimpse into the mindset of Formula 1 engineers.

At every moment, they are trying to find ways to improve on what’s gone before whilst technically staying within the confines of the regulations.

Whilst DAS might be the most recent example of designers trying to steer the car in an unconventional way, it is not the first.

Steering is an area of the car where engineers have tried to probe the limits, with various solutions having been tried – and many of these subsequently getting banned. Here we take a look at some of the most famous examples.

All steer

Williams had been enjoying a spell of superiority during the early 1990’s and it seemed that everything they tried turned to gold.

Benetton B193B 1993 rear-wheel steering schematic overview

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

In a response to rumours that it planned to add to its impressive arsenal of electronic aids with a rear wheel steer system for 1994, Benetton rigged its B193C test mule with a crude rear wheel steer set-up for a test at Estoril.

The results were inconclusive as to whether it added performance. But the team decided to add another string to its bow for the last two races, and continued to test it with both of its cars fitted with the system.

It was a system that could be deactivated and should the hydraulic lines be compromised a fail-safe would return the wheels to the straight ahead position. The team ran the system during free practice on both occasions but opted not to race it.

These trials proved to be enough of a stimulus for the governing body to get ahead of the game and ban four wheel steering ahead of the 1994 season before the practice got out of hand.

The fiddler

McLaren MP4-13, third pedal

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

McLaren found another way of steering the car later that decade, adding an additional pedal that would control the rear brake caliper on one side of the car and help to pivot the car under braking.

The team ran this brake-steer solution during the latter phases of 1997 and into 1998 before it was famously discovered by photographer Darren Heath, who’d spied the brakes glowing when they shouldn’t during cornering and resolved himself to find out what was amiss.

He took his chance at the Luxembourg GP as both McLarens retired and he was able to get a shot in the footwell of Hakkinen’s cockpit, revealing the slender extra pedal on the left hand side.

The extra pedal was set so that it needed more pressure applying to it, so that it could not be accidentally used. It offered a way of being able to balance the car when transferring to it from the main brake pedal.

This not only helped the driver to dial out the inherent understeer the car had, but also had a first unthought of aerodynamic benefit. With the car being pointed by the rear of the car, the front wheels did less steering, something that’s helpful when we consider the damage that could be done aerodynamically by the wake turbulence created by the front wheels.

For 1998 McLaren had improved upon its initial system, as previously it had to rely on braking only one rear wheel with the fiddle brake. But it added a switch in the cockpit that enabled the driver to select which of the rear brakes the pedal would operate.

The system was banned in the aftermath of its discovery, with the other teams lobbying for its removal on the basis of it being a four wheel steering system.

Push and pull

Mercedes AMG F! W11 DAS ackerman details

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

The arrival of DAS during pre-season testing just highlights that even with the tightest regulatory constraints ever seen, teams are still more than able to outmanoeuvre the regulators.

A point proven when James Allison – Mercedes technical director, remarked about DAS in a recent Q&A on the team’s YouTube channel, suggesting it actually wanted to introduce it a season earlier.

But, having spoken to the FIA, the governing body wasn’t happy about how Mercedes planned on it being deployed by the driver.

During the Q&A, Allison confirmed that the initial design had a paddle on the steering wheel as a control mechanism, rather than pushing and pulling on the steering wheel.

The more convoluted steering column mechanism came about as a result of a consultation period with the FIA who, according to Allison, probably believed that it was too much of a challenge to overcome and would likely result in Mercedes ditching the idea entirely.

Mercedes decided otherwise though, as Allison explained.

“We have a very inventive chief designer, John Owen, and he took one look at that challenge,” he said.

“He’s got a really good gut feel for whether something is doable or not, and that’s a really helpful characteristic, because it allows us to be quite brave spending money when most people would feel the outcome was quite uncertain.

“John took that challenge on, reckoned he could do it, put it out to our very talented group of mechanical designers, and between them they cooked up two or three ways in which it might be done.

“We picked the most likely of those three, and about a year after that, out popped the DAS system that you saw at the beginning of this season.”

Other teams have opposed the use of the system, with Red Bull going as far to say it would protest it in Australia, had the race happened.

However, from a regulatory standpoint, it’s clear that Mercedes will be allowed to use its DAS system throughout 2020 – unless Red Bull or another team challenge its legality with the stewards. The regulations have already been amended for 2021 so its use will be prohibited from then anyway.

Mercedes AMG F1 W11 & W10 comparison

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

Comparing the W10 and W11 shows some of the changes made by the team to include their DAS system for 2020.

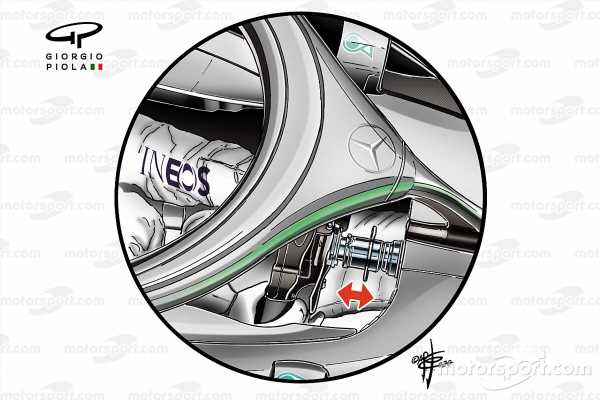

Mercedes AMG F! W11 DAS ackerman details

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

A close-up of some of the details, most specifically those connected to the steering assembly.

Ferrari SF90 front detail

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

Ferrari introduced its ‘PAS’ system at the French GP, the two different versions of its steering assembly that can be seen here alongside the chassis for comparison. Their ‘PAS’ system is a passive version of what Mercedes have and similar to their 2019 system, i.e. they don’t have a mechanism to change the toe/Ackermann angles.

Source: Read Full Article