The depth and breadth of the illustrative archive of Giorgio Piola really knows no bounds, with the legendary Formula 1 illustrator having captured 50 years of the sport’s technical endeavors. Join us as we continue to take a look at some of his favourite cars and this time venture into the excess and decadence of the 1980s – this time, the Brabham BT52.

Click on the arrows below to scroll through the images and captions…

BT51: The Brabham that never raced

Photo by: Sutton Images

The BT52 was a car born of necessity, rather than the continued development of a well-proven concept. The team had readied the BT51 for the 1983 season, which it considered a further refinement of the ‘ground effect’ design concept that teams had been using for a number of years. Downforce and power levels had reached dizzying heights, and so the FIA felt compelled to act and with just weeks before the start of the 1983 season. Changes to the regulations forced teams into a last-minute redesign. However, with the design of the cars intrinsically linked to the ground-effect concept, it was huge hurdle for the teams to jump in such a short period of time.

Goodbye ‘ground effect’

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

This fabulous cutaway of Brabham’s BT49C from 1981 is part of Piola’s extensive illustrative archive and shows how the lower portion of the sidepod was shaped like an inverted wing, while the exterior paneling and skirt prevented airflow from escaping or ingressing in order that more downforce could be generated.

Dart-shaped wonder

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

Brabham’s chief designer Gordon Murray took one look at the new regulatory format and knew that long sidepods with inverted wings beneath them, that worked so well when sealed, would be disastrous if carried over to the new car. He decided on a totally different approach to his rivals, opting for this iconic dart-shaped silhouette instead.

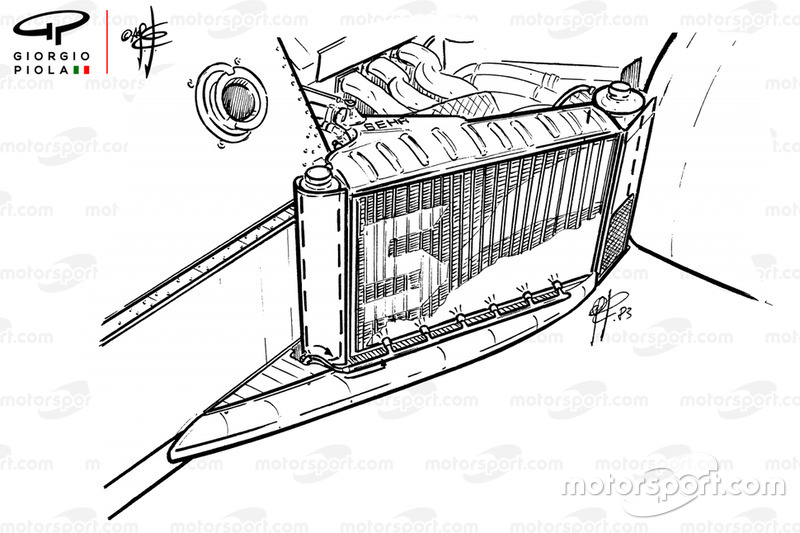

Brabham BT52B 1983 radiator detail

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

Perched on top of the dart-shaped rear section of the BT52 were the radiators and intercooler, which were charged with cooling the turbocharged BMW engine sat beside them. Married to this philosophy was a significant rearward shift in weight and more rearward positioning of the rear axle, improving the car’s traction given the engine’s enormous power output.

Brabham BT52B 1983

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

By happenstance the regulation change had come at a point where Murray was looking to incorporate a modular design concept, allowing the whole rear end to be assembled away from the car, then bolted on when ready to go. Knowing the powerful but grenade-like BMW engine run by Brabham was typically junk after each session, Murray packaged the engine, intercooler, radiators, gearbox and suspension into a self-contained unit, allowing them to be bolted and unbolted from the car’s rear end.

Then as now!

Photo by: XPB Images

The concept was a milestone in Formula 1 design and was swiftly copied by rivals but perhaps more importantly it’s still fundamental in the construction of modern-day F1 challengers, as it allows the mechanics to work more efficiently on separate parts of the car rather than tripping over one another.

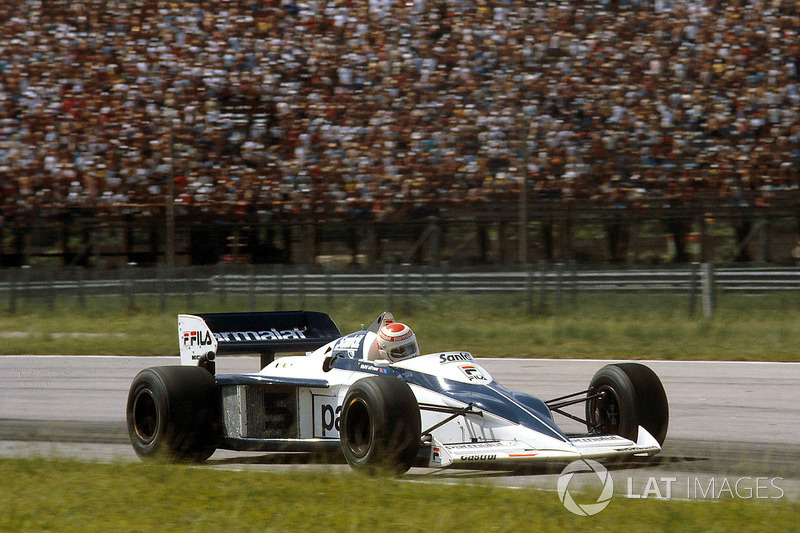

Tank attack

Photo by: LAT Images

Murray had also taken the opportunity to rework the car’s fuel tank, having already utilised a smaller tank for the 1982 season when Brabham would routinely refuel during the race – a decision that seemed visionary once everyone switched to mid-race refueling for ‘83. However, the other teams still had full-size tanks, a decision that would result in a taller engine cover and more disturbed airflow to the rear wing, giving Brabham another tangible advantage.

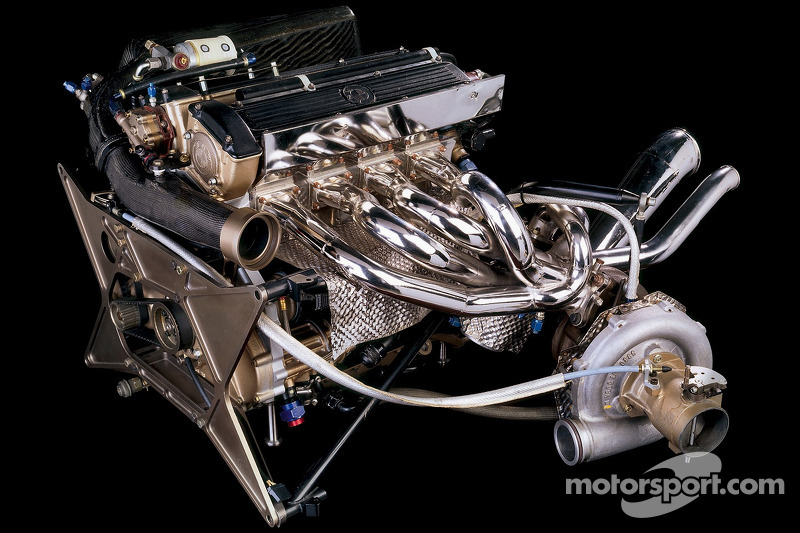

The power behind the glory

Photo by: LAT Images

One of the undeniable factors in Brabham’s success was the use of the monstrously powerful BMW engine, which was producing in excess of 1300bhp. It’s a staggering figure, even in today’s terms, and one that could not have been reached without the assistance of fuel supplier – Wintershall. It developed an exotic mixture that would aid in knock resistance and improve combustion.

Chemical energy

Photo by: BMW AG

The regulations surrounding fuels were relatively archaic at the time, requiring that they only share commonality with fuel commercially available at the pump. This gave BMW, Wintershall and latterly their rivals plenty of wiggle room when it came to the fuel’s chemical composition. So they set about raising the calorific value of the fuel, in order to increase the engine’s compression ratio, raise boost levels and reduce detonation. Toluene is often cited as the key ingredient used by the fuel suppliers, given its octane boosting properties, but clearly the chemical composition featured other ingredients in this potent and high-energy mixture.

World champions again

Photo by: LAT Images

The combination of Murray’s ingenious approach to the late change in regulations and the most powerful engine on the grid left us with one of F1’s most mesmerising designs. The BT52 was a fast and agile challenger that took its maiden victory at the first race of the season and finished on the podium twice more in the first eight races. But, it was when the ‘B’ spec car arrived at the British GP that things really intensified, as Nelson Piquet went to battle with Alain Prost (Renault) and Rene Arnoux (Ferrari) for the drivers’ title. The team went on to add three more victories and a further four trips to the podium in those closing races, with Piquet able to clinch his second drivers’ title at the last championship round as Prost and Arnoux both retired from the race.

The cutaway diagram of the Brabham BT52B from Giorgio Piola’s extensive illustrative archive is now available for you to own – click here.

Source: Read Full Article