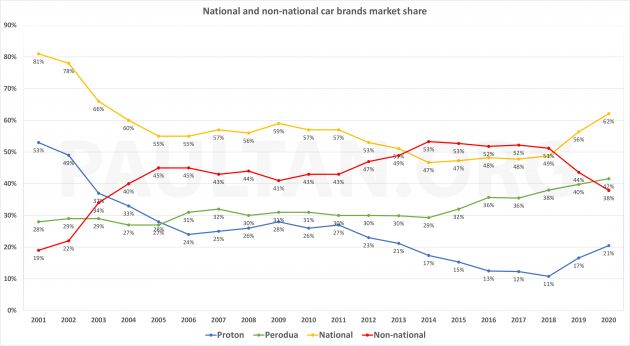

National brands Perodua and Proton have seen their combined market share rise in the last few years, propped up by continued strong sales by market leader Perodua and the revival of Proton, which reached its nadir of 11% in 2018. Their combined 62.1% share of 2020’s total industry volume (TIV) is the highest since 2003.

With six out of every 10 cars sold last year being a Perodua or Proton, the slice of the pie for non-national marques is shrinking. From a high of 53% in 2014, where foreign brands overtook P1-P2 for the first time ever, the trend held firm till 2018 (51%). However, the rise of Proton in 2019-2020 ate into the non-national share, and 2020’s 38% is the lowest level for NNs since 2003 (34%).

We pointed out last week that this was not always the case. In fact, when we were covering the 2014 TIV, the breaking news back then was the non-national brands overtaking P1-P2 for the maiden time. Buoyed by an on-form Honda (2014 sales were up 50% year-on-year), foreign brands were looking up. P2 chiefs attributed the shift to market liberalisation and raised alarm back then.

Then, the national brands’ steady decline was entirely down to the poor performance of Proton, which saw sales and share slide from 2011 until the Geely era (P2’s share hovered consistently above the 30% mark for a decade beginning 2006, so it was pulling its weight). It was a time when the Japanese big three brands were aggressive in the B-segment, introducing new models with entry prices that encroached into the top end of traditional Proton/Perodua territory.

The Protons of that period – the Preve C-segment sedan, its Suprima S hatch sister, and the Myvi-fighting Iriz – didn’t put up a good fight. Here, we take a look back at the non-national models that capitalised on a weak Proton, and the rise – and subsequent fall – of Honda, Toyota and Nissan. To make it interesting, we included Mazda, which strategies and targets differ from its larger counterparts.

The Power of Dreams

In this rise and fall story, the main protagonist is Honda. One should never underestimate the power of dreams, but we’re betting that when Honda Malaysia was established in 2003, the bigwigs there never dreamt that it would one day overtake Toyota in Malaysia, never mind passing Proton to be second in the sales charts.

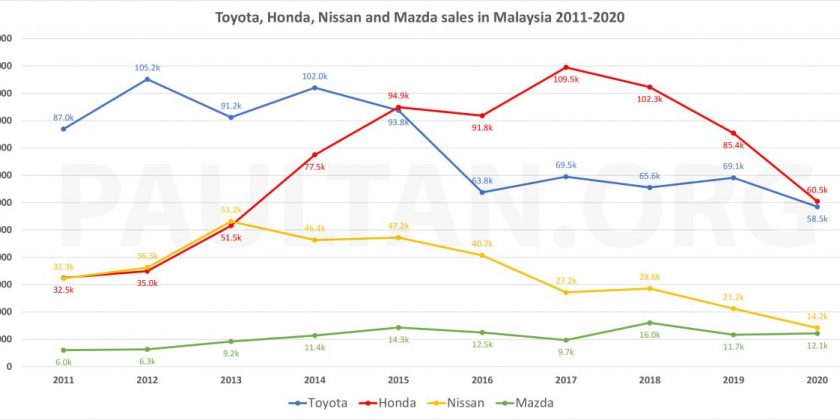

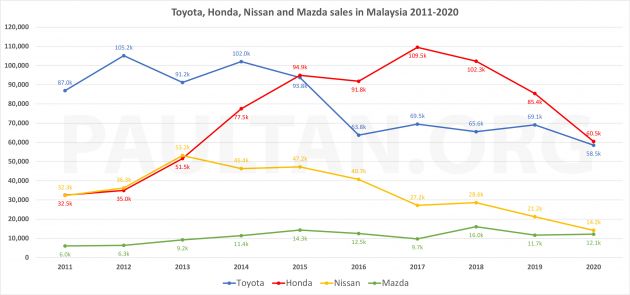

Honda did exactly that, pipping Toyota to the No.1 non-national spot in 2015, a position it has since held, although 2020 was a photo finish in its favour, just like in 2015. Momentum was strong, and Honda went on to do what was previously unthinkable – in 2016, it deposed Proton to be No.2 overall, a position it managed to occupy till 2018.

The climb was steep – just see the red mountain in the topmost chart. Back in 2012, Honda sold fewer cars than Nissan, and while both surged in 2013, Honda still ended the year below Nissan (51,544 vs 53,156). It was heady days for Toyota then, flirting with the 100k mark and occasionally getting the goods (105,151 in 2012 and 102,035 in 2014). But just two years after it was sparring with Nissan, Honda overhauled the big T to be the top foreign make in Malaysia.

How did that happen? Think of the fourth-generation City, which debut in March 2014, as VTEC kicking in. The sedan, which truly moved the B-segment game on, was joined by its Jazz sister hatchback in July. These new entries boosted Honda sales by 50% in 2014. The following year would be the first full year of sales for the two models, and volume jumped by a further 22%. The GM6 City went on to be the most successful generation ever, outselling its arch-rival at the end of its lifecycle.

Everyone needs a breather after a sprint, and 2016 was one for Honda, before it continued the journey to the peak. The brand’s 2017 sales of 109,511 units (19% up) wasn’t just its personal best, but the highest annual total ever for a non-national brand in Malaysia. The fact that Honda doesn’t sell pick-up trucks like the rest of its NN rivals, makes its sales feats even more impressive.

Honda started bright and early in January 2017 with the launch of the BR-V, before the hot selling City and Jazz duo were facelifted (Hybrid option added). The current-gen CR-V joined the range mid year, while 2017 was also the first full year of sales for the landmark Civic FC, which debut in mid-2016. Quite some year it was for the company.

When you consider the recent momentum swing towards national cars, Honda’s 2017 feat, or 100k sales for that matter, is unlikely to be ever repeated again by a foreign make in Malaysia.

What goes up…

Must come down. Sales in 2018 retreated slightly (6.6%) from the previous year’s high point, but were still above the 100k mark. 2019 was a troubled year for Honda, which was severely affected by product delays that were out of its control. The facelift of the very successful HR-V filled up many vacant carparks before it was finally launched, and the Civic facelift didn’t make its original 2019 launch schedule (they finally got it out in February 2020, and then MCO happened). Sales fell to the lowest point in five years (85,418).

If in the past, the Japanese were encroaching into P1/P2’s territory with entry-level offerings, the opposite is true now. Proton’s Geely-powered rejuvenation has seen it gone upmarket – the stylish X50 and X70 SUVs are direct rivals to the HR-V and CR-V, with national price perks to sweeten the deal. If not for the X models, surely many of these new Proton customers would have gone down the default SUV road, and that path leads to Honda.

You can swap out X50/X70 and HR-V/CR-V for Myvi and Jazz, too. Perodua hit the ball out of the park with the third-generation Myvi that surfaced in late 2017. Whatever the Myvi loses out in brand power and refinement to the Jazz, it makes up for it in equipment. Priced RM20k less than the base Jazz S, the top Myvi AV trounced the entry Honda in convenience (LED headlamps, touchscreen HU, digital AC) and safety kit (six vs four airbags, VSA, AEB). A lot more for a lot less – many heads were turned.

Just like low and high tides, carmakers don’t come out with winners all the time, and the good models tend to clump together like a striker’s purple patch, vice versa (think Civic FB and the fourth-gen CR-V). Sometimes, the life cycles of various models come together nicely and opponents are not at their strongest; with that ideal combo, Honda Malaysia conjured up a great team goal in 2017. One for the ages, but probably never again.

While it retained the No.1 non-national spot last year, Honda’s 60,468 units sold in 2020 was its lowest since the days that it was duelling with Nissan. Is there a way back up? Well, this year will be the first full year of sales for the latest City, and the new Jazz-replacing City Hatchback might arrive to bolster the attack, so we’ll see.

Did Toyota try hard enough?

If that sharp drop was Honda, the top non-national brand, then the sales of the others must have dived into the ground? Not really. Toyota’s pain happened in 2014-2016 and it has had the last few years to bed into a new normal. Nissan’s N17 Almera boost lasted them four years before a stepped decline began.

As you can see from the chart on top, Toyota was on a high level in the first half of the decade, even breaching 100k twice. However, since losing out to Honda in 2015, its decline was swift – 2016 sales was down by a whopping 32% to 63,757 units, and it has stayed in the 60-70k band ever since, save for 2020’s small dip (58,501 units).

Playing a major role in the fortunes of the carmakers here are their B-segment sedans. Deliver one that flies off the showroom floor and your bonus next year will be fat, generally. Get it wrong however, and your rival with the more popular B-sedan will take advantage.

Toyota didn’t get the third-generation Vios wrong per se. In fact, the XP150 – nicknamed “keli” (Malay for catfish) for the shape of its mouth/whiskers – even beat the GM6 City to the launch tape by nearly half a year when it surfaced in October 2013. The body was new, but this Vios carried over the long-serving 1NZ-FE and 4AT powertrain combo, and the 2,550 mm wheelbase.

Toyota’s bread and butter car finally received a new engine in 2016, giving the 1NZ-FE (which has been in the Vios since the nameplate was born in 2003!) a well-deserved retirement. In its place is the NR series engine shared with Perodua. In 2019, the Vios received a major overhaul, which gave it the look of a new gen. No changes under the skin, but that’s to be expected as the powertrain was updated in 2016. Another facelift was launched in December 2020.

If it sounds confusing, you’re not alone. Instead of a clear-cut generation with a facelift three/four years on – which is the default life cycle – Toyota opted for a series of running and overlapping changes. Even as the familiar Vios soldiers on with new clothes for 2021, the Honda City – which debut later than the Vios in the previous round – has moved into an all-new generation.

We’re in no position to tell Toyota that they played it wrong, but the fact that the previous-gen Honda City comfortably outsold the then newly-overhauled Vios in its final full year of sales (2019), points to the victor. It’s definitely not for the lack of marketing on Toyota’s part (the Vios had a star-studded one-make race as part of an annual nationwide roadshow), so perhaps Malaysian carbuyers wanted more from the product? What do you think?

Bear in mind that UMW Toyota Motor – with Malaysia’s relatively small volume next to giants Thailand and Indonesia – won’t have the biggest say at the ASEAN table (to put it lightly), and many things are decided en bloc, regionally.

City vs Vios aside, Honda had a big sales contributor over the past few years in shape of the HR-V. When the compact SUV arrived in 2015, it single-handedly created its own segment in Malaysia, even if B-SUVs existed before that. Toyota’s answer to the HR-V was the C-HR, a fine car and product hampered by CBU-derived price/spec issues. It made negligible impact to the overall sales cause as a result.

Another two sizeable segments that were free runs for Honda is the C-segment SUV – where the CR-V is a class stalwart (Toyota’s RAV4 finally arrived in 2020, but as an expensive CBU Japan import) – and the B-segment hatchback, where the Jazz has been a great wingman for the City. Meanwhile, the Toyota Yaris hatch has been an occasional silent visitor in pricey CBU form until 2019, when today’s CKD model was launched with competitive pricing.

Put two and two together and it appears as if Toyota handed the initiative to Honda, who then took it with both hands and ran as fast as it could.

A two-speed race

If you look at the chart, the big gap between Honda and Toyota has all but evaporated and it’s all to play for from here on. Further down, Nissan’s steady decline from the N17 Almera-induced high (2013) has seen sales drop to Mazda’s levels in 2020 (14,160 vs 12,141). It now looks like a two-speed non-national race – Honda vs Toyota for third/fourth, and Nissan vs Mazda for fifth/sixth.

That sort of volume would be quite worrying for Nissan, as Tan Chong’s business footprint in Malaysia is much larger than its 2020 sales would suggest. The long-time local partner of the Yokohama carmaker has a range of locally-assembled models and operates two factories in Malaysia. If this is the new normal volume for the brand, one wonders if it’s sustainable for TC – perhaps that’s why the company is now looking towards China for diversification.

It’s a whole story by itself, Nissan in Malaysia, but the brand’s current state is probably a combo of the principal’s product strategy for the region and the local partner’s occasional perceived hesitancy. The latter is often used as a point of criticism, but one must remember that Tan Chong is not Nissan, but essentially a customer of the principal – you’ve got to commit certain numbers to get a product at a competitive price, and if that bet doesn’t pay off, the losses are all on you as the assembler/distributor.

What about the new Almera? It looks the best of the B-segment lot (to me at least), and there’s even tech to match (downsized turbo engine, active safety kit), not something you’d say about the dumpy old model. But unfortunately, the price has also crept up (RM80k onwards), so it’s no longer the default budget option. Here’s hoping the N18 does well.

Things couldn’t be more different for Mazda and Bermaz. One of the few brands to have recorded a growth in 2020, last year’s volume is double that of a decade ago. Unlike Nissan, Mazda is largely a CBU company, with only the CX-5 and CX-8 SUVs – its volume sellers – being locally assembled for domestic and ASEAN consumption. Also different from Nissan-ETCM’s case is Mazda Motor Corp having a majority stake in the manufacturing business in Malaysia.

In urban areas and more affluent neighbourhoods, Mazdas are part of the street furniture. Many probably don’t realise this, but walk around Tokyo or Osaka and you’ll struggle to spot a Mazda – even luxury imports are more common there. I can imagine executives visiting KL from Hiroshima being in awe of the brand’s outsized presence in Malaysia.

Without the scale to CKD everything, Mazda trades on design and premium positioning – with the slice of the non-national pie expected to continue shrinking over the coming years, Mazda’s approach to life in Malaysia might do it good. With the confidence accumulated from growing the Mazda brand in Malaysia, Bermaz is now teaming up with Berjaya to repeat the trick with Peugeot.

With Honda-Toyota and Nissan-Mazda now neck-to-neck in the sales league, who will you put your money on to prevail at the end of 2021? And with Perodua’s anticipated D55L SUV coming soon, as well as the Proton X50‘s first full year of sales to account for, how much more will the non-national pie – now at 38% – shrink? It will be an interesting year ahead, that’s for sure.

Research Honda Cars at

Source: Read Full Article