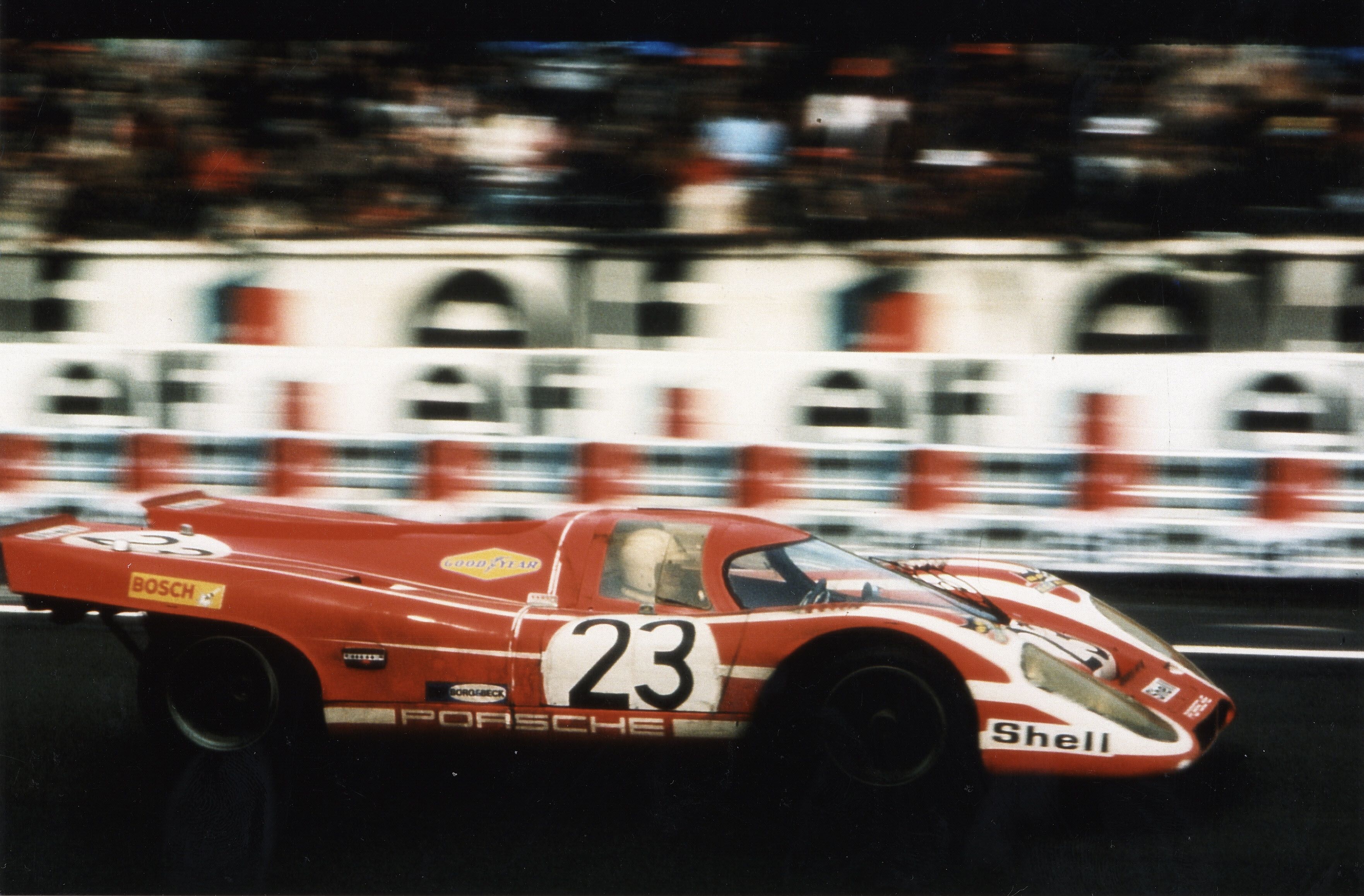

Last year, Porsche invited Road & Track to Sonoma Raceway to drive a handful of its finest historic cars. Among them a 917, and Richard Attwood on hand to make sure it was being driven properly. Attwood—who turned 80 this past weekend—and Hans Hermann drove a 917 to victory at the 24 Hours of Le Mans 50 years ago. In honor of Attwood’s birthday, we’re publishing his conversation with Editor-at-Large Sam Smith about the car. The following has been edited for length and clarity. -Ed.

Sam Smith: One of the interesting things about this car is how its story has just been told so many times. It’s part of the pantheon—this group of unassailable greats, discussed endlessly.

Richard Attwood: I know.

SS: It’s been fetishized, it means so much to so many people. Is that hard to get your head around? I mean, it’s just a car. You guys used it as a tool. Almost disposable.

RA: Well, they’re not going to get written off now, are they? I think it was posted last year—Motorsport magazine named it the most enigmatic competition car of all time. But it was a very charismatic era, wasn’t it? Where we got the two competition makes, if you like, in sports-car racing, Ferrari and Porsche at it together, you know.

For that, for the Steve McQueen film [Le Mans], it emphasizes that. Although in period, it bombed. Didn’t do well, was over budget, cost a fortune. But it ended up… it’s like a documentary. I never realized until the last couple of years. The first 45 minutes or so of the film…

SS: There’s no dialogue!

RA: No dialogue at all! You can’t believe that, but it actually does seem to work.

SS: A friend once described it as a ski film, or a skateboard film, but for racing. Like those things they project onto sheets at parties. Just eye candy, guys dropping into moguls or waves for hours, only this is race cars. Artful shots of a gone era.

RA: Yeah.

SS: Is it strange to look back on that part of your career—because that’s what it was—and revisit it that often? Journalists, authors, historians, all they want to talk about. To focus so much on something from early in your life?

RA: Mmm hmm. I think things like that, they’ve got to affect you at the time. Your recollection of something really outstanding or weird or exciting. And if you didn’t experience that, you’d [be sitting there thinking] Wow, is that really true?

SS: The cars are now so valuable that even exercising them is just a massive financial risk. Is it better for something like this—deeply rare, valuable, expensive to operate—to be locked away and safe? Or exercised and shared?

RA: It shouldn’t be resided in a museum and not used. No. I mean, a lot of people have said that. And they made such a wonderful noise as well. I mean, the more cylinders you have on an engine, the better it sounds. [Laughs.]

SS: Rumor has it you’re lucky enough to drive one of these things maybe once a year now.

RA: Yeah, probably twice a year, actually. Usually through the Goodwood events. I drive for Porsche anyway. Employed by them for odd jobs. Have been for some time now. I always do the Festival of Speed, the one around [the Duke of Richmond’s] house. There’s usually a 917 amongst the cars there. In fact, this last time, I drove two different 917s. Because there were half a dozen of them there, and there’s now a lot of private owners who want to be a part of that event. And Charles March is very interested in cars like that. I myself, as well!

SS: There are famously a lot of variants of this thing. Bodywork, engine tune, as Porsche tried to figure the cars out, make them work and go quicker and safer. Are there good ones and bad ones any more, or are they all at the same level at this point?

RA: Yeah. But you’d really only know if they were good or bad if you had to race them, I suppose. And we don’t do that. So to get to know any 917, really, any more, I wouldn’t know? The difference between one or the other. Except one might be more comfortable than the other.

Here, at the [Goodwood] Festival, we don’t push. We might take it up off the line, but the biggest influence on the car—and particularly, on the Festival—is all the slow-running stuff. You’re messing about, going from A to B and another car park, and then the run up the hillclimb, waiting. So the likelihood of a car starting to misfire is very much what influences any [opinions] now.

SS: How well it’s tuned and sorted?

RA: I mean, this one here, it’s always on 12 cylinders.

SS: Makes sense; it’s a factory-prepped car, and they own it.

RA: They’ve done some things to it in a modern way that makes sure it does serve, that the car in festivals will be fine. But a normal car, which has the old ignition packs and everything else original, will eventually break down during something like the Festival. Which is a three-, four-day event. It’s just slower, and you don’t have a chance like you have here, to blow it through.

SS: Which is…

RA: Eventually more fun with that. I had a 917 for 20-odd years. I used to run my car at Goodwood, and I ran it on a high-performance BMW plug. It wasn’t a racing plug, it was a projected-core plug. And they would break down, actually, at about 7000 or 7500 rpm. Which actually is brilliant, ’cause it acted, you know, like a rev limiter. It was perfect.

SS: On an engine worth more than most houses. If you actually own a car like this, use it, are they reliable? Are they hugely expensive to run?

RA: Uh, nothing much.

SS: Really?

RA: Well, the big advantage is, it’s air-cooled, so you haven’t got any water in it. Corrosion is not the problem. I never had any problem at all—it literally is just a turnkey operation. You could leave it for the whole of winter—which I did at my house—in the barn, and you know, with all the animals and mice and things around there. And you put a battery on it, and you turn it over, and it starts.

SS: You kept yours in a barn?!?

RA: Hmm.

SS: That’s just so great. Most people wouldn’t, is all. They’ve become such pieces of jewelry.

RA: Well, I wanted to hang onto the car, and nobody really was interested in putting it in a showroom at that time. There wasn’t the interest there is now.

I did have it down at Reading, at Porsche Reading, the main headquarters for Porsche Great Britain. I had it there for a while, but they got fed up with it. Wanted something new or different. So I had it at home mostly. And the barn. Didn’t matter as much, because it was fiberglass body. A really easy car to keep.

SS: When was all this?

RA: Through the Eighties, primarily. I didn’t own it until 1976. Maybe ’78. Bought it from [fellow works Porsche driver] Brian Redman. He found this car in Germany, in a garage, must have been a super-duper garage. They repaired what was effectively a [botched] engine, where the valves and everything else got mixed up with the brakes and camshaft drive. Did a really good job. And the repair bill came into the owner, and he couldn’t afford to pay it.

So they had to wait maybe 18 months or I don’t know how long, before they could sell the car to retrieve the cost. Brian happened to hear about it. As soon as I knew he bought it, I said to him, “Brian, can I have first claim on that car?”

We didn’t know the history on that car. At all.

SS: But I take it you found out.

RA: Yes, we knew exactly. It was the Solar Productions camera car.

SS: The one that they used to film much of McQueen’s Le Mans.

RA: It was in the film. It didn’t have a great history in racing, although it did finish fourth and sixth in world sports-car championship races.

SS: That gap, you say, where the world wasn’t much interested in these cars. What kicked it back over?

RA: Well, the world was different then. When a race car became—whether Formula 1 or sports car—when it was noncompetitive, or the regulations had changed, it was just obsolete. And that was really all it was. The world wasn’t interested so much in the history of cars. And I’m not talking about 917 Porsches. Any car—prewar, Grand Prix, postwar. They’re the big values now, but the escalation of prices is almost insane. Investment opportunities that never were before.

Because what’s the point of having an obsolete car? But the world’s changed massively.

SS: You think there’s going to be a moment where everything shifts back the other way?

RA: It’s already happening, really. There are people who race them now. And the Lola T70, I suppose the nearest equivalent to a car that raced a lot, and it’s really successful. You go buy an engine for it, it’ll be a 2019-spec engine. But that’s a much easier car to get bits for. Parts for 917s are scarce and very expensive. And people who own bits for them, they know how valuable they are.

But prices will fluctuate, as they do on the world market. Just like works of art. Although the best works of art do always sell well.

SS: In period, did the car seem as special as it does now? Or was it just another device for a job?

RA: To me, it was special, and to Brian it was, ‘cause we had driven them, and we fancied owning one. And Brian sold his, because he had another project in life and he bought a different house. He’s regretted it ever since, and I’ve regretted selling mine ever since as well.

But when I sold my car in 2000, at the Monterey RM auctions—nobody was that interested in it. They got to just over a million dollars, and then the bidding stops.

SS: Oof.

RA: The traders didn’t rate this or value it any higher than that. I said to RM, ‘So if I don’t get a certain figure, you know, I’ll just take it home.’

But actually, I didn’t do that, as I had run short of money. And the question was, Do I sell my house, or do I sell this car?

SS: Oof, again.

RA: And the car was easier to move.

SS: And it was.

RA: It was a wrong thing to do, but no one was to know they would go up in value 20 times from then. So if I owned it now, I’d be maybe $15 million richer, but, I don’t!

Source: Read Full Article