When NHRAPro Stock Motorcycle’s Karen Stoffer won in September 2019 at St. Louis—sharing the winners podium with Pro Stock’s Erica Enders—she said, “What you saw with Erica and me speaks volumes to everybody, not just women. If you have the passion, if you have the will and the ability, you can come out here and do what you want to do. You can progress so that you can win.

“Handicap, height, weight, gender, nationality . . . it doesn’t matter. The NHRA is so diverse in every capacity. (Everyone’s) talking about women and gender. But you also have height and age. We had Reggie (Showers), who has two amputated legs. There’s no prejudice in this sport—at all, zero,” Stoffer said. “Anybody in any capacity can come out and race in this sport, and I think it speaks volumes. It doesn’t have any gender favoritism. Everybody can go down this race track.”

For decades, the NHRA easily, unquestionably, has been the leader in motorsports—if not all sports—in diversity on every front: gender, race, age, heritage, ability, socio-economic status, and even skill.

As long as a person has earned a license in the appropriate class and has a race car that passes tech inspection, he or she is permitted to enter competition. Even part-time racers—drivers who make a family outing of an appearance or don’t have any intention of chasing a championship—are welcome. They sometimes are among the more popular entrants.

The NHRA has had women who are champions, including multiple-time champions (Erica Enders, Pro Stock, 4; Shirley Muldowney, Top Fuel, 3; Angelle Sampey, Pro Stock Motorcycle, 3). Brittany Force also has one Top Fuel title.

Antron Brown, who is black, has three championships in Top Fuel, and JR Todd, who is biracial, has a Funny Car championship. Hispanics have won five titles: brothers Cruz and Tony Pedregon two apiece in Funny Car, Hector Arana one in Pro Stock Motorcycle. Former Top Fuel driver Khalid al Balooshi, of Dubai, has a Pro Modified crown. And Japanese nationals have won key rounds and races: Kenji Okazaki had his flashes of brilliance in the late 1990s, and Yuichi Oyama ended Kenny Bernstein’s career at Pomona, Calif., in November 2002, as he reached the final round that day.

Fans truly pay little attention to distinctions among competitors.

But for all the comfort with diversity in the NHRA, some of the racers recognize that they aren’t operating in a quarter-mile Camelot. Just as in life outside the drag strip, prejudice has popped up in occasional offensive incidents.

Top Alcohol Dragster driver Jasmine Salinas is a global ambassador for drag racing and a strong advocate for women in every walk of life through her video documentary Five Foot 280. The recently released four-minute, 44-second video (named for Salinas’ height and the speed at which her race car travels in a pass) was selected by five American film festivals from coast to coast and has been nominated for Best Documentary Short by the London-based International Motor Film Awards.

But as much as she calls herself “so fortunate and grateful to have this opportunity to have this hobby where it’s something that empowers me,” Salinas can see room for improvement in the sport.

She said, “I constantly hear—and it’s mostly from male racers and fans—that drag racing is so diverse and so welcoming of women. And it is. It’s an incredible sport, and I never felt more like I belong. But still, as a woman in a male-dominated sport, from being in a Jr. Dragster to doing Top Fuel or Pro Stock,” she said she sees an environment that’s not always fair.

“You still get, because you’re a woman, men feel(ing) that when they want to bring you down they usually target women’s physical appearances—versus men, it’s usually not targeting physical appearances. That’s extra baggage women have to carry being out there that men never have to experience,” she said. “I don’t care how welcoming and diverse the sport is. It doesn’t mean that those comments aren’t being said and that women aren’t experiencing things.”

Her 21-year-old sister Jianna had a rough rookie season in Pro Stock Motorcycle in 2019, including a top-end tumble from her bike during eliminations in June at Chicago. By the season finale that November, Jianna Salinas had earned the trophy. She did it in an unconventional way, winning each round because of her opponent’s mistake. Jasmine Salinas said she and the family rejoiced, naturally, but it was even more emotional a moment because of how Jianna was treated by some.

“She had so many people after her crash just consistently giving her all these comments and remarks and messages (through the anonymous protection of social media), attacking her: everything from she shouldn’t be there, she’s a woman, she just sucks. It was something she was just struggling with every time she was at the track,” Jasmine Salinas said. “Even though she wasn’t breaking records at Pomona, the fact that she was able to get through the race and finish the win and finish the year like she did, it was really special as her family to see her get through that.”

Brown, universally liked for both his driving skills and engaging personality, couldn’t escape a flare-up of racism—from his own teammate. When he accepted the first of his three championship trophies, the other racer used a racial slur for which he was fired. The incident was downplayed as a matter of that teammate bringing his own supply of alcohol into the NHRA awards ceremony. The offending driver apologized, at least for his poor conduct, and spoke of wanting to “be a better person.” Brown never initiated a stir about it, and the incident faded away.

But Brown had to deal with race that championship-winning night in 2012, as the milestone-hyped media quizzed him about being considered the first black Top Fuel champion.

“I never sat back and thought about it,” Brown said, but he said he’d be happy “if I can be an inspiration for other kids out there—not just African-Americans, just Americans period—give them somebody they can look up to that’s positive that actually never settled in life for things that people told them they may not ever achieve.”

Enders, who recently wrapped up her fourth Pro Stock crown in seven years and became the sport’s most decorated female champion, understands Brown’s point, not from the angle of race but of gender. She said her achievement “is a goal I set as a child, that I wanted to be the best race-car driver on the planet, not just female (race-car driver).”

Funny Car’s Cruz Pedregon won at Englishtown, N.J., in 2014 to tie legend Don “The Snake” Prudhomme on the class victories list. He said then that Prudhomme (who has referred to himself as a Cajun) has been his hero because they both have battled prejudice.

“I’ve identified with Prudhomme because I don’t look like all the other drivers,” he said. “As a kid, I recognized that name and his accomplishments, but hey, you take off the helmet off (and) I can identify with him more than a blond, blue-eyed guy. That’s all I’m sayin’. I’m in a sport where, other than my brothers, there are no Hispanic drivers.”

Actually, Hector Arana has raced alongside both sons, Hector Jr., and Adam, in the bike class. Top Fuel’s Mike Salinas and his two daughters have Hispanic heritage, and the four Cuadras in Pro Stock—dad Fernando and sons Fernando Jr., Cristian, and David are Mexican nationals. But certainly Pedregon is right in saying he’s part of a minority segment in the sport.

Pedregon said being unique has helped.

“(It’s) why sponsors identify with certain minority groups and women drivers, as well,” Pedregon said. “When they take the helmet off, there’s not the regular, everyday-looking guy. So I have felt that has worked to my advantage, to a certain degree, with sponsors. Now, with Prudhomme, I felt like it was a double-edged sword, because he was a champion. He was a winner. So naturally, he got the behind-the-scenes ‘ribbing.’ Just like in school: if you’re different-looking or (have a) different skin color, there’s the critique.

“I’ve been around, in my inner circles—being around the race teams I was around as a crew guy—Prudhomme . . . I’m going to be honest . . . not to his face, but there were racial undertones there, in a way just to poke fun at his look – but because he was winning and beating everybody,” Pedregon said. “And I feel like that’s a part I experienced. I’m not going to get into the specifics.

“You can separate yourself and have sponsorship opportunities, if sponsors are looking to appeal to the diverse crowd. You’re going to stick out,” he said. “You’re also going to be a target for racial discrimination. What do I mean by that? You can take it 1,000 different ways. You cave in and feel bad about it. Or you say, ‘Hey, they wouldn’t be talking about me if I was not a winner.’ So I identified wit Prudhomme in that respect, and I’ve always felt like that.”

Several others have spoken up against injustices and highlighted drag-racing’s authentic, organic diversity.

Funny Car owner-driver Bob Tasca is a third-generation owner of a network of auto dealerships in the Northeast and works with a cross-section of people in his stores. His employees represent diversity, with women and minorities among his general sales managers, sales managers, technicians, and sales and administrative staff. And that’s how he approaches his racing operation: performance, not appearance, is paramount.

“I don’t care what color their skin is. If you get the job, you’re going to perform—or you won’t be in the job,” Tasca said. “Whether it’s in racing or dealerships, I’ve never, ever had anyone say to me, ‘You can’t hire this person because he’s black.’ Never. And if anyone ever said it to me, he wouldn’t be standing in front of me that long. It’s just never happened. I’ve never looked at skin color—it’s never crossed my mind as negative.”

D’Andre Redfern, one of the few black mechanics in drag racing, works on Tasca’s Ford Mustang. But Tasca said, “How many black technicians (at the dealerships) do we have? I don’t know. It’s not a number on my desk. It’s not something that we measure, because there’s no cap on it. There’s no limit . . . just whoever’s in the market and wants to work for us and can do a good job. The color of someone’s skin or gender doesn’t even come into the conversation.”

But Tasca isn’t naïve. He said, “The harsh reality is that racism exists. We have to acknowledge it exists. There’s no magic wand to come up with the perfect answer. The good people of the world have to do more to prevent it, because it’s unacceptable. It’s not who we are as Americans or who we were meant to be as human beings. I will do my role in whatever I can to live up to those values I was born and raised on. Whatever I can do in my small circle of influence, I try to do. We can all play a bigger role in doing the right thing. That’s what it comes down to.”

And regardless of the occasional blemish on the NHRA’s record, Tasca said, “I’m very proud of what we represent as a sport, as a sanctioning body, and how we represent diversity. Our sport’s a great example for other sports to look at.”

For as desperate as NASCAR and as eager as the IndyCar Series have been to build a platform of diversity, the NASCAR- and IndyCar-centric media largely have ignored the well-established and sustained accomplishments of women in the NHRA.

A perfect example was the reactions of every major news outlet in February 2013. The same day Danica Patrick secured the pole position for the Daytona 500 and triggered “DanicaMania,” a continent away at Pomona, Calif., Courtney Force won the Winternationals from the No. 1 starting position and set the quickest elapsed time and top speed of the meet in Funny Car. And she received not one word of either record or distinction from any major print outlet (other than one covering the Winternationals that day) and nothing from national TV networks.

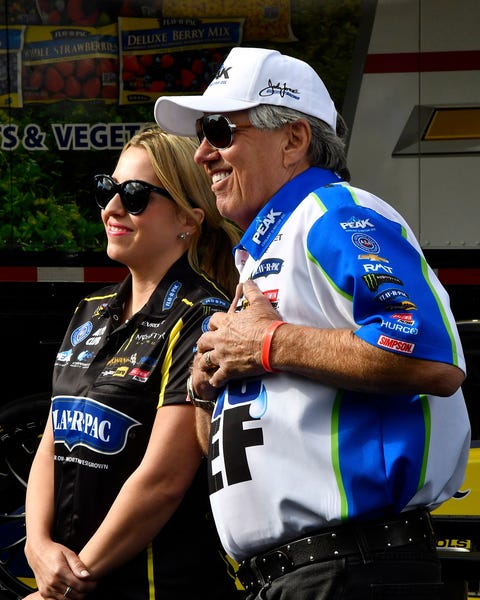

Her father, 16-time Funny Car champion John Force, told The Arizona Republic’s Michael Knight the next week (when Erica Enders won in Pro Stock and Patrick drove to an eighth-place finish at Daytona), “I get that Danica got the pole is a big deal, but it’s not like she delivered the baby Jesus.”

NASCAR legend Richard Petty said back in 2006 that auto racing is no place for women: “It’s really not. It’s good for them to come in. It gives us a lot of publicity. It gives them publicity. But as far as being a real true racer, making a living out of it, it’s kind of tough.”

It is tough, but Enders had some news for him.

She replied, “There are some people that are stuck in the old day and that are chauvinistic and I think it just goes to show . . . their ignorance. When given the opportunity . . . we can definitely prove ourselves. I think gender plays absolutely no role in what we do.”

Several years later, Enders beat NASCAR champion Kurt Busch in his NHRA Pro Stock debut at Gainesville, Fla. She said, “When you put the helmet on, everything’s equal. I don’t care if you’re Kurt Busch or George Bush. I’m going to do the same thing I do every Sunday. Hopefully, he will go back and tell his NASCAR buddies how tough it is to race NHRA Pro Stock.”

Three-time Funny Car champion Robert Hight agreed with Enders.

Hight said, “Every competitor is the same. A girl can do it just as good as I can.” And this past February, he applauded the return of Alexis De Joria to the class: Good to see her back. Really just shows her love of the sport and couldn’t stay away. I can see that, and I really respect her for that.

“She can do a lot of things in her life, whatever she wants to do. She chooses NHRA drag racing, and that’s my kind of girl.”

Is there any other sport as diverse as the NHRA? Why don’t we see a more diverse field in NASCAR or IndyCar? Start a conversation in the comments section below.

Source: Read Full Article