Earlier in June 2018, anyone driving on the highways near the city of Wichita, Kansas might have caught a glimpse of what seemed to be a UFO on the back of a large flatbed truck. What they were actually looking at is part of the work being done to answer the very important question of just how long an F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is supposed to last before it’s no longer airworthy. So far, the U.S. Air Force’s F-35As and U.S. Navy’s F-35Cs look to be as durable as expected, but tests on an example of the U.S. Marine Corps’s F-35B have exposed more serious issues.

On June 6, 2018, the F-35 aircraft, an A model, arrived at Wichita State University’s National Institute for Aviation Research, or NIAR, as part of the Joint Strike Fighter program’s durability testing regimen. Manufacturer Lockheed Martin had sent the jet from its Fort Worth plant to the research facility so that specialists could tear it down and inspect its internal structure to determine whether it had adequately withstood earlier tests. At present, the F-35A, B, and C are all supposed to have a lifespan of 8,000 flight hours.

“As part of the F-35 program, durability ground test aircraft undergo exhaustive testing to validate the structural integrity of the airframe to withstand a variety of maneuvers it will experience throughout its lifetime,” NIAR said in a statement to the Kansas Department of Transportation. The latter organization also released images and other information about the plane on the back of the truck to allay any possible public concerns.

A truck carries an F-35A ground test article to Wichita State University’s National Institute for Aviation Research in June 2018.

This isn’t the first time NIAR has helped analyze the results of structural and durability tests on F-35 aircraft. In August 2017, the facility received an F-35B model for inspection. The institute also performs a wide array of other aviation testing services for the U.S. government and private companies and hosts two additional centers that it operates in cooperation with the Federal Aviation Administration and the U.S. Air Force.

Lockheed Martin has built a total of six ground test articles, two of each of the three F-35 variants, to support these experiments and has been actively stress and fatigue testing the airframes since 2009. The company and its subcontractors have used a host of different test stands and other equipment to drop and otherwise simulate typical operations and maneuvers that the aircraft will experience during its expected life cycle.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=h6BsCvDgbsc%3Frel%3D0

The U.S. military’s central Joint Program Office (JPO) for the Joint Strike Fighter has mandated that testing put each type of jet through testing that simulates the equivalent of three full life cycles, or 24,000 flight hours.

This doesn’t mean that each one of the test F-35s will go through that full amount of abuse or that contractors can’t perform normal, expected repairs and preventive maintenance during the experiments. The objective is to simulate typical use, not simply shake the airframes apart. Lockheed Martin only set aside one of each type specifically for ground fatigue testing, as well. The other three aircraft have gotten subjected to different kinds of stress tests, including getting shot at to see how the airframe might hold up in combat.

One of the ground test F-35Bs, known as BG-1, after a live-fire experiment.

The F-35A that arrived at NIAR in June 2018 had just finished the third cycle of tests for that variant. The F-35C was slated to finish its final round of testing in December 2017, but it is unclear if that has occurred and when analysis of the results might begin.

“For all variants, this testing led to discoveries requiring repairs and modifications to production designs and retrofits to fielded aircraft,” the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation, or DOT&E, reported in its most recent annual review of the program, covering the 2017 fiscal year, which ended on September 30, 2017. This is, of course, exactly why the U.S. military conducts these tests in the first place.

But while the F-35A and C variants look set to meet the stated durability goals, the Marine Corps’ F-35B has had considerably more trouble. The F-35 JPO suspended durability testing on that variant in February 2017 after one of the two test articles finished the second simulated life cycle, according to DOT&E.

“Due to the significant amount of modifications and repairs to bulkheads and other structures, the program declared the F-35B ground test article was no longer representative of the production aircraft, so the JPO deemed it inadequate for further testing,” the Pentagon testing office’s report noted. “The program canceled the testing of the third lifetime with [the F-35B known as] BH-1 and made plans to procure another ground test article, but has not yet done so.”

An F-35 undergoing stress testing.

It is very likely that the F-35Bs structural woes are, in no small part, due to a massive effort early in the Joint Strike Fighter’s development to cut the weight of that variant in particular. Beginning in 2004, a group of engineers at Lockheed Martin called the STOVL (Short Take Off/Vertical Landing) Weight Attack Team, or SWAT, found ways to shave more than 2,700 pounds off the Marine Corps’ version. They trimmed 1,300 pounds from the A and C types, too.

This weight reduction project was critical to advancing the program at the time, but persistent reports of cracks in bulkheads and other components, along with other issues, have raised questions about what got sacrificed to meet those targets.

Now, there is a very real concern that the B variant may not meet the 8,000 flight hour target. These jets may have a shorter service life than the other types “even with extensive modifications to strengthen the aircraft,” DOT&E warned.

On top of that, these versions are having serious problems with the durability of their wheels specifically. Unlike the F-35As and Cs, the B models have the ability to take off and land vertically, which requires tires that are at the same time durable enough for a conventional landing and soft enough to cushion the jet when it comes straight down.

As it stands now, ground crews have to change the tires, on average, after fewer than 10 full-stop conventional landings, which is less than half the target number. Lockheed Martin has reportedly sourced a possible replacement tire design, but will only begin testing it sometime in late 2018, according to a report on the F-35 program that the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a congressional watchdog, released earlier in June 2018.

A US Air Force maintainer repairs the tire from an F-35A.

Ensuring that the jet’s airframe, as well as other ancillary components, last as long as they’re supposed to, is extremely important for both safety and sustainment reasons. Without an accurate understanding of when the planes will literally fall apart, the U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marines Corps, as well as foreign operators, could risk putting pilots in the cockpit of aircraft that simply aren’t airworthy.

It is also an essential component for long-term planning with regards to sustaining the F-35 fleets since these tests will provide additional data on what components are most likely to fail and when. This, in turn, can help give an early sense of what portions of the airframe might need an overhaul or outright replacement, and how much that might cost, during any service life extension program down the road.

The Air Force is already in the process of starting a major life extension project for its F-16C/Ds, as parts of that fleet begin to get near their maximum allowable flight hours. The U.S. Navy is similarly embarking on a similar program to breath additional life into its F/A-18E/F Super Hornets.

Having a good understanding of the structural lifespan of the F-35 could be even more important given the inherent complexities associated with any heavy maintenance on the jets due to their stealthy features. Delays and other setbacks for the Joint Strike Fighter Program, which have extended its development time overall, mean that these issues could come to the fore sooner rather than later, too.

All three variants of the F-35 flying in formation.

On May 30, 2018, the U.S. Navy, which leads the F-35 JPO at present, awarded Lockheed Martin a contract worth more than $45 million to, in part, to “support service life extension” work on the developmental test Joint Strike Fighters. The oldest members of this fleet of aircraft, which now numbers more than a dozen in total, have been flying for more than a decade already for testing purposes.

An accurate appraisal of how long a lifespan each of the aircraft has will also be increasingly important as the U.S. military looks to move to full-rate production of the aircraft. With more jets coming off the production line, the cost to implement any necessary, but complex structural fixes or improvements will similarly grow.

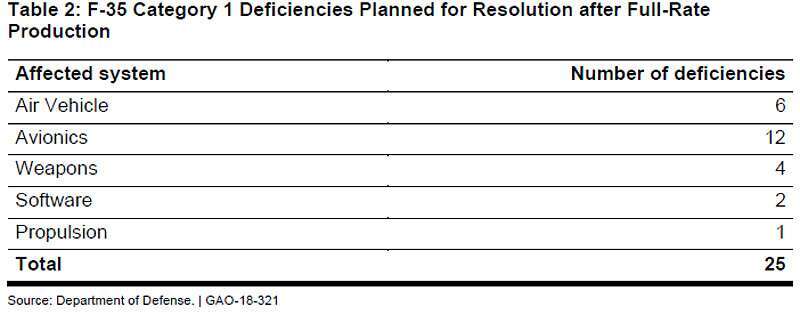

The aforementioned GAO report was highly critical of the Pentagon’s push to move ahead and step up production without having first fixed a host of unspecified serious deficiencies with the aircraft, including six having to do with the “air vehicle” itself. The review noted that the JPO did not have a well-established plan for how and when to integrate any upgrades into existing and future aircraft as part of its Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2) concept, either.

A table from the June 2018 GAO report on the F-35 noting that there are six significant “air vehicle” deficiencies, among other issues.

The report also pointed out that the JPO has yet to give a full accounting of the costs associated with bringing jets up to the “final” Block 4 standard and building new ones in this configuration or what those aircraft will actually look like in terms of mission systems and capabilities. Any major changes in the aircraft’s structure or other components could change the stressed on certain portions of the airframe and potentially have an impact on the aircraft’s overall lifespan.

It’s worth noting that the JPO determined the existing F-35B ground test article was no longer suitable for tests due to how much the airframe had changed over the course of previous experiments. It did, however, accept the results of the second round of testing.

Not knowing the specific conclusions from the existing testing on any of the F-35 variants, it’s hard to judge how significant the impact of the repairs and configuration changes may or may not have on the jets’ life expectancy. With regards to the F-35B, what may happen is that it could simply end up with a shorter official service life than the other two variants.

If the actual lifespan is closer to 6,000 flight hours, this would put them on par with the U.S. Navy’s F/A-18E/F Super Hornets, which are now slated to get upgrades to extend their lives out to 9,000 hours. The U.S. military will still need to buy another F-35B to be sure, though.

As of yet, inspectors have not yet formally certified any of the three versions as having an approximately 8,000 flight hour-long service life. In the meantime, until these important figures get settled, residents of Wichita and the surrounding environs may continue to see F-35s under wraps heading to NIAR so specialists can examine them.

Contact the author: [email protected]

Source: Read Full Article