The ACO and FIA—organizers of the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the World Endurance Championship, respectively—confirmed on Wednesday that they will officially bid farewell to the space-age prototype class of race cars after the conclusion of the 24 Hours of Le Mans in June 2020. The launch of the next championship, the 2020-2021 “Super Season,” will fill the LMP1 void and feature the back-to-the-future “Hypercar” formula as the top WEC class.

In shifting away from LMP1, the ACO/FIA will abandon the incredible—and incredibly costly—machines that defined the mid-2000s diesel revolution of Audi and Peugeot, as well as the more recent hybrid era where Audi, Porsche, and Toyota famously budgeted hundreds of millions each year to create the world’s fastest prototypes. Only Toyota remains in the current LMP1 manufacturer game; it’s left to fight among “privateer” non-hybrid LMP1 teams working with a fraction of the Japanese factory team’s technology and money.

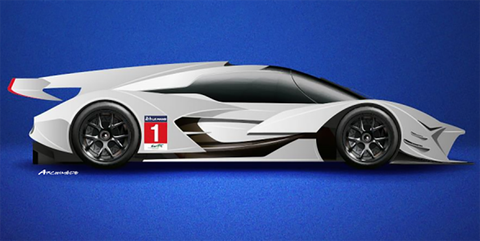

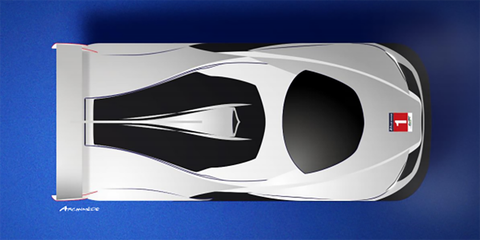

What’s coming in late 2020 takes a page from the GT-style prototypes that raced at Le Mans in the late 1990s, and by all accounts, today’s decimated LMP1 class should be revived by a retro-modern form of the concept.

FIA-WEC

What it is, and what it isn’t

We’ve had suggestions and inklings of what the Hypercar formula would contain, but large swaths of facts were missing. Now that the rules have been published, here’s what we can say.

To start, we still don’t know what the class will be called. “Hypercar” is the generic name being used until the ACO/FIA conduct a fan poll to pick the proper name. For the sake of clarity, “Hypercar” will be used here to refer to the LMP1 replacement class and “supercar“ will denote high-performance road vehicles.

Unlike the McLaren F1 and other supercars of the 1990s that were welcomed to compete at Le Mans with suitable racing and safety modifications in place, Hypercar 2020 has nothing to do with dressing up production Bugatti Chirons, Pagani Huayras and the like with racing gear and entering the FIA WEC.

Engines and hybrid energy recovery systems taken from production supercars, however, will form the basis of the new class. Leave the rest of that Ferrari FX666 Extravagante (or whatever it’s called) behind, though, because a custom racing chassis built to 2020 Hypercar specs is required.

Enough leeway has been granted on the chassis side to give every manufacturer a chance to create something that looks unique, and carries whatever production supercar styling cues the company wants to employ. Simply put, while a road-legal Pagani won’t be welcome in 2020, the Italian firm could build a racing chassis that bears a resemblance to the Huayra, outfit it with a race-modified engine from the same car, and seek an ERS partner to fit the required hybrid system to the ACO/FIA vehicle.

And if Pagani or any other brand was more interested in supplying Hypercar engines and ERS systems than building whole race cars, the ACO/FIA are open to that limited scenario. Secure an engine/ERS supply, buy a Hypercar chassis (likely to be built by a specialist racing constructor like Dallara, Ligier or ORECA), install the propulsion bits, and you’re in. Competing vehicles could take the form of a full factory effort, with Hypercar chassis and engine/ERS from an automaker like Aston Martin, Ford, McLaren, SCG, or dozens of others. Or it could be a blended scenario where a customer chassis is mated with a manufacturer’s go-fast units—think Dallara-Lamborghini, Ligier-Bugatti, or ORECA-Volvo, as fictional examples.

Cool cars, limited costs

To prevent manufacturers from building purebred Hypercars that only exist in the world of racing, there are a few safeguards in place. Auto manufacturers of all sizes are meant to vie for overall wins at a fraction of the peak nine-digit LMP1 budgets. Something in the $23 million per year range—at the low end—is what the ACO/FIA envisions for a two-car team. Manufacturers will still be able to spend themselves into oblivion, but the new rules and the way those rules will be governed are designed to eradicate any major drivetrain or aerodynamic advantages gained through prolific spending.

That proposed $23 million figure represents a healthy reduction in spending, the one area that has historically been the leading killer of factory programs and major racing series.

Real-world track testing (compared to driver-in-the-loop simulators, simulation software, shaker rigs, etc.) will be slashed to lower operating expenses, and among the many curious notes offered by the ACO/FIA, a limit of 40 technical staff members for a two-car team has been listed among the cost-cutting plans.

Whether the latter stands up against labor laws in the European Union is worth following as we get closer to 2020.

FIA-WEC

Size and volume

There’s an unexpected blend of freedom and restriction in the Hypercar technical rules. For those who loathe spec race cars, this should offer some salvation.

Slashing costs almost always coincides with a downturn in technological fun, and to their credit, the ACO/FIA have struck an interesting tone for smaller marques and auto giants alike.

The most encouraging entry from the 2020 regulations is offered in the section for engines: “Engine cubic capacity is free.”

The largest-displacement Le Mans entry from the modern era that comes to mind was a whopping 10-liter V8 wedged into an ex-Corvette IMSA GTP chassis. More recently, Porsche dominated all prototypes by going in the opposite direction with the 2.0-liter turbo V4 that powered the 919.

Turbocharging is allowed in Hypercar. Rotary engines, unfortunately, are not. If it lacks reciprocating pistons, it lacks an invitation, but if you want to stuff a Mopar Death by Displacement crate motor in a chassis and go play at Le Mans, have at it. Restraint in overregulation with Hypercar engines is among the finer qualities of what’s coming for 2020.

As a whole, the final Hypercar rules confirm the intent to abolish bespoke racing engines from the conversation. While the big LMP1 manufacturers made motors that were both unobtainable to privateers and existed nowhere but the WEC, the new rules demand a stock block approach to Hypercar. As the rules state, “At least 25 engines identical to the ones destined for the production car homologated for road use equipped with this engine must have been produced” by the end of 2020. That number increases to 100 by the conclusion of 2021. This is where the ACO/FIA police the race-to-road angle.

Digging deeper

There’s also some fun to be found in the regulatory minutia. In the interest of saving weight, Hypercar engine suppliers are permitted to cast new blocks and heads from lighter metals, provided they come from the production motor’s original castings. Another attempt to keep costs down has been implemented here: A minimum engine weight of 396.9 lbs is in effect, and it’s a message that says don’t bother with exotic materials unless you’re trying to carve pounds off an iron monstrosity.

We have a few other items that could fall in the positive or negative department, depending on your internal combustion engine leanings: Four valves per cylinder is the limit, with two inlet and two exhaust as the only option, but crankshafts design is left wide open. A petrol four-stroke engine is required, with no electromagnetic or hydraulic valves allowed, which could limit the interest of a company like Koenigsegg. A spec fuel supplied by the ACO/FIA will replace any of the recent freedoms in that area.

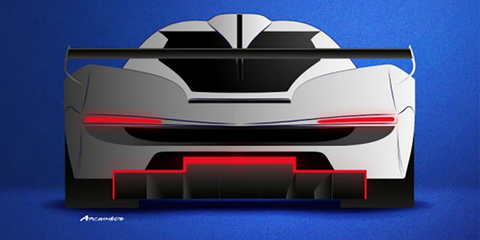

Another choice that could entice or repel manufacturers is the strict power output specified for Hypercar. It’s 681hp. Not 682, or 683. It’s 681.239hp, to be exact. And it must be directed exclusively to the rear wheels. As with the internal combustion engine, strict homologation rules are applied to energy recovery systems, where a power limit of 268.204hp will be enforced for electric ponies.

The ERS system is restricted to driving only the front axles, and while two generator units are allowed, they must connect to a mechanical differential that doesn’t vector power output. Contrasting the unholy ERS systems found in LMP1 cars, the ACO/FIA have lopped 300-400hp or more from the craziest ERS units seen in the WEC. Piggybacking on the simplified Hypercar engine plans, ERS systems will lose much of their complexity in a bid to reduce costs.

Owing to an expectation for full factory Hypercar efforts to compete alongside smaller independent teams that buy or lease part or whole cars, a rental option has been created where privateers can access factory ERS systems to outfit a two-car team for the season at a price of $3.4 million. That assumes, of course, that a factory team like Toyota will want to make its ERS systems available for rent. To date, factory LMP1 teams have been mostly unwilling to let the little guys gain access to their elite machinery.

FIA-WEC

Venturing into stupidity

Elsewhere in the 100-plus pages that detail the 2020 rules, norms and oddities abound. Minimum vehicle weight? That’s 2294lbs. Weight distribution? 48.5-percent to the front, minus fuel and driver, with a 1.5-percent variance allowed. Why paint weight distribution into such a tight box? Good question; plenty of answers can be offered, but few make sense at the moment.

And on the subject of weight, the most arcane concept in sports is coming to Hypercar: “success ballast.” The name is perfect: with success in each race, excluding Le Mans, weight will be added to the cars that earn points for finishing towards the front, to slow them down in subsequent races. The ACO/FIA will apply 1.1lbs of weight for every point earned, up to a maximum of 110.2lbs of ballast.

While Equivalency of Technology (EoT) and Balance of Performance (BoP) measures are in place today in ACO/FIA and other series to try to equalize cars with different engine types or aerodynamics, success ballast is the first systemic effort to penalize teams’ quality performances.

Assuming a similar point structure is used in 2020, a win today is worth 25 points, second place earns 18, third gets 15, etc. Since extra weight will slow a car, it seems like teams will be given a valid reason to “tank,” in a slight degree, to avoid receiving maximum points and the maximum weight penalty that comes with it.

Picture your favorite football or basketball players being fitted with ever-heavier weight belts based on how many touchdowns they score, yards they run, or three-pointers they drain while out-performing most of their opponents, and you have the model coming to ACO/FIA endurance racing in 2020. Only in sports car racing would making the winner of one race the biggest loser for the next become an actual rule.

The fallacy here involves penalizing the cars that succeed without taking into account how the rest of the organization—drivers, pit crew members, engineers, etc.—affect the outcome of a race. Fortunately, there’s still time for the ACO/FIA to think through some of the items it has announced and fix the silliness before 2020.

A final question

Seeing 2020 Hypercar Aston Martin Vulcans (or Valkyries, possibly) blast around Le Mans or Spa, fighting McLaren Sennas and Mercedes-AMG Project Ones for the lead, would be amazing to behold. But would it be more enjoyable than watching race-prepped versions of road-based cars like, say, the Devel Sixteen and Rimac Concept Two EV go wheel to wheel in FIA WEC competition?

I’m confident that what’s coming in 2020 will attract new fans to sports car racing, and the reason for the newfound interest will come from the names involved in Hypercar and the general looks of the Hypercars.

Where I lack confidence is in the way the ACO/FIA have erased the genuine performance differentiators that make actual roadgoing supercars so compelling. How many versions of the Ferrari vs Bugatti vs Porsche-style videos and articles have been produced that celebrate these cars’ diverging approaches to making speed?

Drag races, time attacks, and all manner of holy-shit car vs holy-shit car competitions have captivated a new generation of auto enthusiasts. Take a quad-turbo W16-powered supercar, see how it fares next to an all-electric 1900hp rocket, and we drool at the otherworldly results.

So what’s the best way to celebrate this rich segment in racing? Limit the maximum engine power to the same number. Apply the same limit to the ERS power. Let the manufacturers know up front that any advantages that emerge with aerodynamics or otherwise will be dialed back to achieve a uniform lap time with the other Hypercar models.

The most extreme form of production cars will be represented in the ACO/FIA’s top racing class, de-fanged, de-clawed, and assimilated to perform at the same level. Co-opting the street supercar concept is a smart marketing ploy; but in a strange twist, the race cars coming in 2020—ones that will bear a likeness to today’s wildest street supercars—won’t be nearly as cool or interesting as their road-going counterparts.

Source: Read Full Article