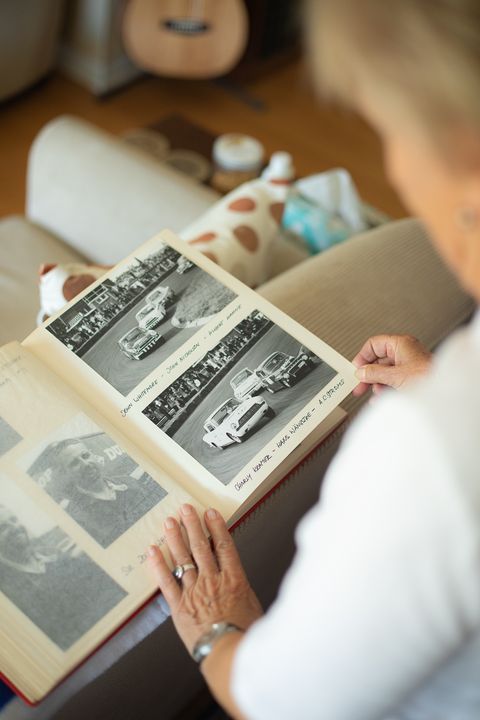

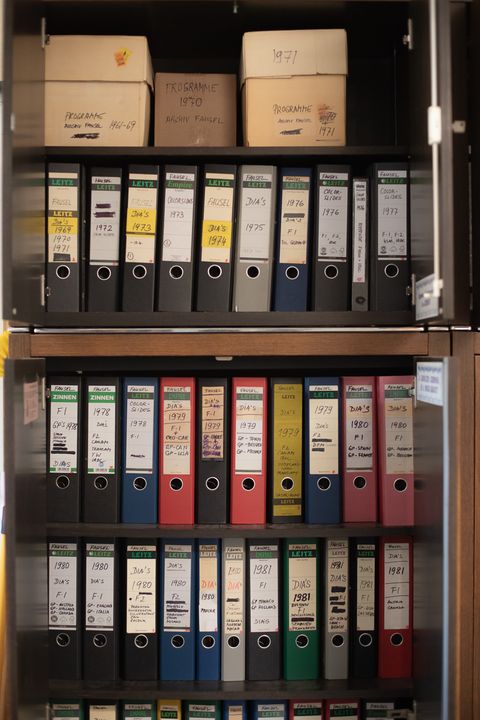

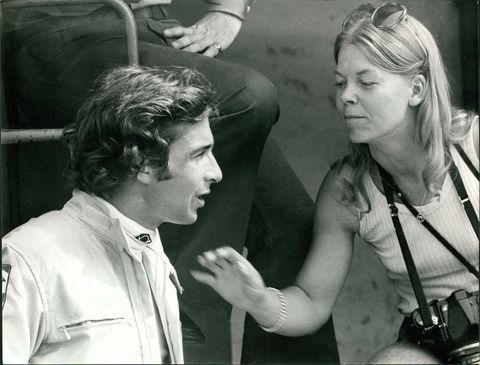

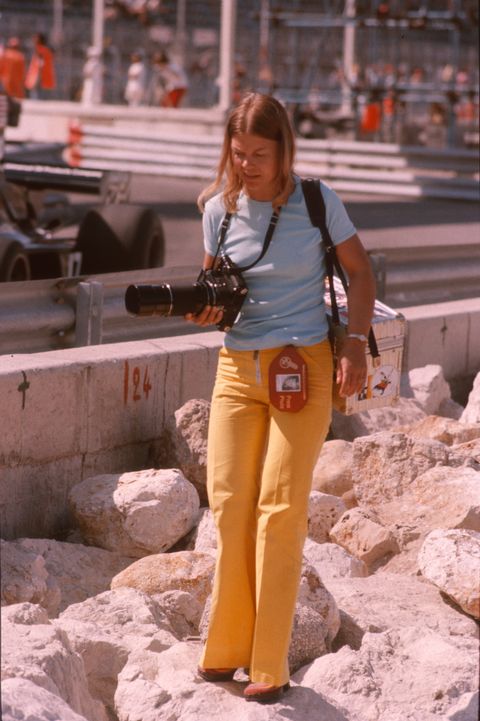

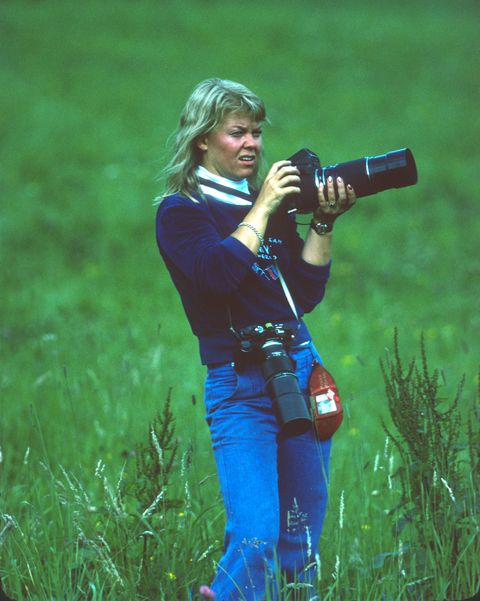

Motorsports photographer Jutta Fausel-Ward opens a notebook to a hand-written list on a single sheet of graph paper that sums up a lifetime of races and shelves and shelves of photographs, totaling a staggering 186,000 images in all. It’s the life’s work of a remarkable yet largely unknown member of what was fondly referred to among insiders as “The F1 Circus,” that travelling show that was part family, part racing organization, and mostly amazing spectacle. Fausel-Ward captured it all and much, much more over a remarkable career that spanned multiple eras of race cars and several generations of drivers.

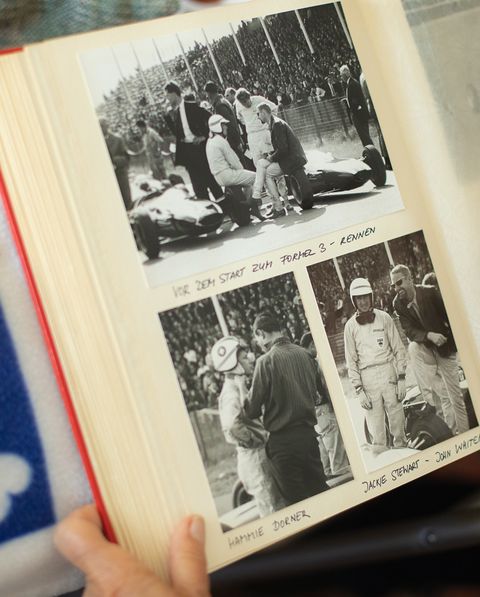

The first F1 race she ever attended was in 1961 at Solitude outside of Stuttgart, where she sat in the stands with a borrowed Rolleiflex camera and shot photos of a distant Jim Clark, Dan Gurney, Bruce McLaren, Jack Brabham, and Jo Bonnier competing in a race won by Innes Ireland. Those first photos weren’t necessarily all that great, but with each one she was learning about her eventual trade.

The next year she was back with a better camera and a telephoto lens borrowed from her boss at the camera shop where she was an apprentice. Not satisfied to merely sit in the stands and not established enough to have a press credential, she snuck into the trees near the track and shot from there, getting images of Gurney and Bonnier in their Porsches and other drivers in Cooper and Lotus race cars. Still not satisfied—and because you could get away with things like this back then—she snuck into the paddock and started shooting photos of the drivers and teams.

“It was fascinating,” she recalls.

Thus began a lifetime pursuit of a racing passion nearly unmatched in the world of motorsports journalism. On that sheet of graph paper it says she attended and photographed 173 Grands Prix from 1963 to 1988, 174 European Formula 2 races, numerous runnings of F3000, F5000, Formula Atlantic, Touring Cars, Sports Cars, Can-Am from 1973 to 1982, the Indy 500 from 1987 to 1994, and countless other series in Europe in the United States and around the world. Those are not just the races she attended, but which she photographed as a professional, and it doesn’t include the World Cup Skiing she shot when the racing seasons were over. That she did from 1977 to 1989.

“My grandfather was a photographer, a war photographer in WWII, and my grandmother and my father told me, ‘A photo always tells the truth,’ which was true.”

She laments modern Photoshop techniques because, “Now it’s not even close to the truth because you can change everything. You change the pimples in the face, you can change the background color. You can take off sponsor names, you can do anything you want.”

That’s not how she learned her craft. Her uncle was also a photographer, not a racing photographer, but he took a lot of photos. One day he took the teenage Jutta to the local photo studio and asked the owner if they wanted or needed a lehrling (apprentice).

“And then she asked me if I wanted to be a photographer and I said, ‘Yes.’”

This was in Goeppingen, near Stuttgart in the late 1950s. Then came the transition from mere photographer to racing photographer.

“A friend bought an Abarth Bialbero and he took me to hill climbs to do some hillclimb races,” she said. “So I had been a few times with him to take pictures to learn to be a real photographer, you know, not only in the office or in the shop but in real life. And so I bought my own first camera, which was a Kodak Retina Reflex with a tele(photo lens). A little tele objective. And that’s how I started to take all the pictures.”

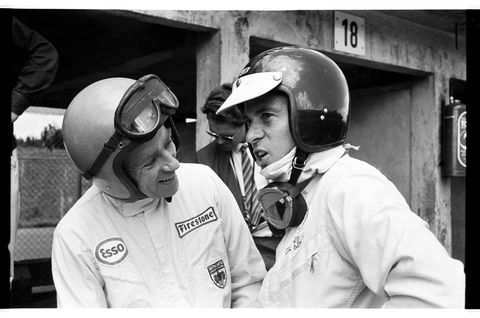

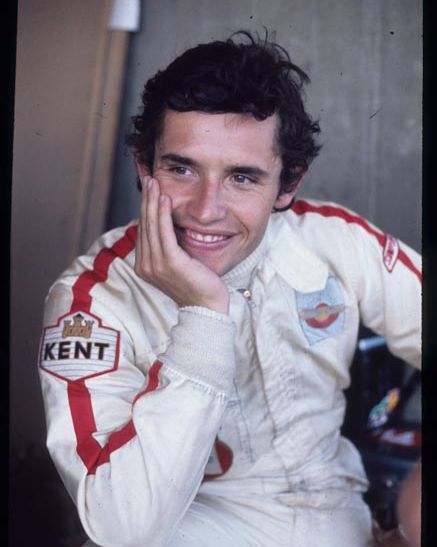

That was in 1960. And soon after that, because no one stopped her, she was shooting Grands Prix, walking right up to Jimmy Clark and Graham Hill and Jochen Neerpasch and Colin Chapman and Bernie Ecclestone and all kinds of great racers who in time were to become her friends.

It was in either 1962 or ‘63 that she turned pro, she said.

“I was at the race and a guy came to me and he had some of my pictures in his hand and said, ‘Did you take these pictures?’ And I was going to be afraid and said, ‘Oh, yes, what’s wrong? What’s wrong with that?’ And he said, ‘I don’t understand you. You’re making these nice pictures and you don’t send it to me.’ He was the owner of Automobilsport magazine.”

“That felt pretty good. I got five Deutsche marks for one printed picture. And I felt pretty good.”

The transition to full-time professional motorsports photographer wasn’t necessarily all that easy all the time. There was the occasional encounter with sexism.

“I went to the Nürburgring for Formula One. And I asked for a press card. And they said, okay. But when I came to the press office they said, ‘Oh, somebody must have picked it up already.’ I said, ‘There’s nobody else but me.’ ‘Yeah, but it’s gone, I’m sorry. You must have, you know, your name is here, but there’s no pass in there.’ So, since I know one of the race directors from Hockenheim, I went to him and said, ‘Listen, you know, do you think this is right?’ And he knows more people and well, in the end, I got a credential. But some bad people hated me then.”

Why did people hate her?

“We were only three women in racing, one from England, one from Italy, and one from Germany, me. And all the others were men. So, it was not always easy… But it got better. It got a lot better.”

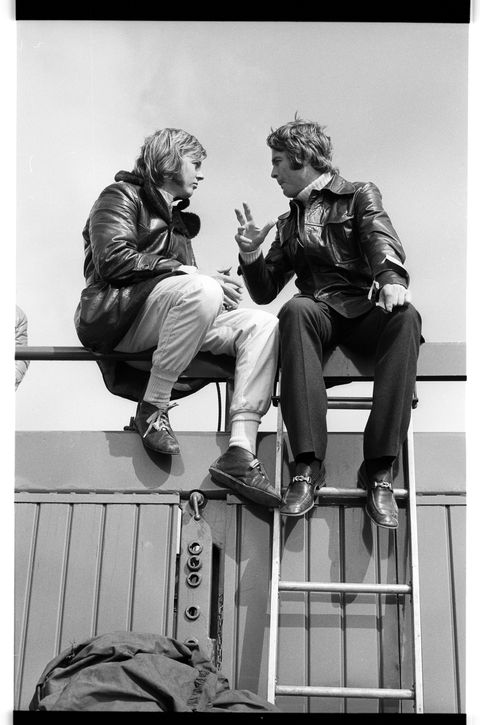

It helped that she knew virtually everyone of consequence in the sport and just about everyone liked her.

“When my colleagues saw me having dinner with Bernie Ecclestone, with Jo Bonnier, or with some of the well-known people from Formula One with lots of money and all that…”

That helped.

“You know, they invited me for dinner. ‘Why don’t you come? Come on.’ So I said, Okay, okay. So I went on my birthday, you know, there was Gordon Kirby and Bernie Ecclestone. There’s them and me on a table at the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa.”

Later there was an invitation from Colin Chapman to dine with the Lotus team. It was more just a familiarity; everyone was traveling around Europe for all these races and you couldn’t help to get to know each other, and so sometimes they all had dinner together.

“My colleagues, they always come along and they’re okay. Colin Chapman, he always had dinners on Friday evenings. They had something for sponsors, you know, and that’s how I met Jimmy.”

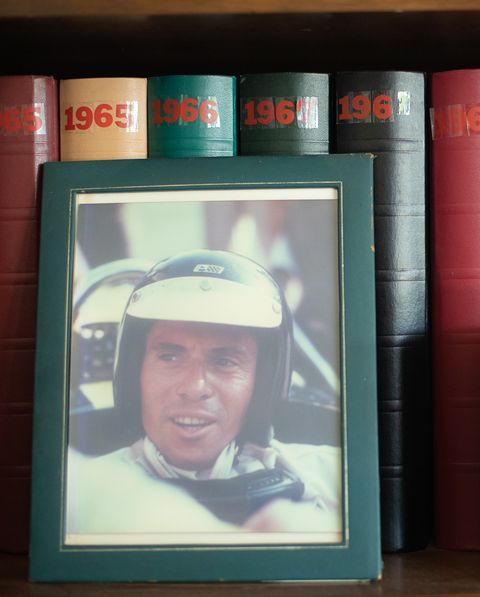

That would be Jimmy Clark, for whom she had great reverence. Who wouldn’t? He was Jim Clark, after all who, even today is on everyone’s list of the greatest drivers of all time.

“Jimmy Clark, he was a little bit my hero,” she said, getting a bite wistful. “Oh, they were all nice drivers. Jo Bonnier, he was nice too. Later on, I met Mario Andretti when he drove the Lotus.”

But knowing the great drivers was also a little bit dangerous, because, in that era, the sport itself was still very dangerous.

“I was there when Pedro Rodriguez was killed (at Norisring in 1971). I saw the whole thing. It was just a little bit away from me. But the Monday after that all the major German magazines called me and wanted to have pictures (of the crash). I said no. No, I would never, ever sell a picture or have a picture published which was from a bad accident. Never, I never did that. I know people who did that, German people and a lot of others, but I never, I never, even if I was in front of them, I would never ever sell these pictures.”

The toughest loss may have been of her friend Jim Clark.

“I would never go out like when Jimmy had that…” She paused, unable to say the word “accident.”

“…at Hockenheim. That was pretty bad. Because he gave me… before he went out he gave me his gloves, his racing gloves, the red ones with ‘JC’ and on the top there. And I was wearing them. It was a cool day. It was slightly raining. And I was out there with a guy from England, with whom I talked sometimes. He was a friend of Jimmy. He wrote the first Jimmy book (Bill Gavin, who wrote The Jim Clark Story). And he was at that race. And we were in the middle of the infield there, shooting. It was lap number seven. And then Bill Gavin came to me. He said, ‘Did you see him?’ I said no. He didn’t come back. So I looked at the start and finish. And I looked at the race director and the racing doctor, who was a very nice guy. And I saw the car going out with the doctor. And when I came to the pit lane, you know, there was the race director and some others. They looked at me and then they said, ‘Come on.’ One of his friends took me to the car. ‘Come on, it’s okay. It’s okay.’ And I know what’s going on. And I didn’t take any more pictures. I just sat there. And then Graham (Hill) came in. He was in the other car, and he said, ‘Yeah, I’m sorry.”

That may have been the hardest part of getting to know so many of the drivers, the cruel fate that could take any of them away at any moment. But it was that sensitivity, that ability to care about and admire her subjects, that was what brought out the best in the photographs she took.

“Every good photographer develops their own eye,” said photojournalist, author, and Autoweek contributor Pete Lyons. “It’s hard to describe, but she had a… you know, if you see a lot of photographs, and then you see a lot of Pete Biro and 20 other people, you get to the point where you say, ‘Oh, I bet Jutta took that one. Yeah, yeah, that’s a Jutta picture.’”

It’s as hard to describe what makes a good photo as it is to shoot one.

“The ones that caught my eye, they tend to be, say, cars coming through S turns, like the two Shadows together nose-to-tail. There’d be Regazzoni, and his teammate Stuck, and the cars are very similar. And there it becomes kind of a, I don’t want to use the word poetic, but that’s the word that’s popped into my head. It’s not just, ‘Here’s another race car going around the corner.’ It’s, ‘Let’s stop and look at these two race cars going through this corner. Isn’t this elegant?’ Whether she set out to do that, I don’t know. I don’t know that any of us stand there thinking we’re going to do poetry today. But you know what you like, and you know what you’re going for. And when you’re finding the location and thinking about it, then you end up with pictures something like that.”

“Did you ever know Pete Biro?” asked race organizer and another close friend of Jutta’s, Chris Pook. “He was he was one of those photographers that somehow had a different vision of what he wanted to take a picture of. I don’t know what it is, an ingredient, these people have in certain photographers can capture certain pictures and a certain light, a certain setting that is, for whatever reason, different than anybody else’s. Pete was one of those people who could do it, and Jutta could do it as well. It’s, I think, it’s almost a God-given talent.”

And remember, this was in ancient times before your Android phone could take a shot and then be used to edit it later with a result that’s better than what 90 percent of photographers could do in the era of manually operated cameras.

“It’s always important to note when talking about a photographer like Jutta, who shot in the era she did, that it was much harder to capture the images she did compared to today’s autofocus, built-in light meter cameras that capture images in RAW files that allow recovery of improperly exposed images,” said photojournalist (and president of Justice Brothers) Ed Justice Jr. “Jutta contributed a number of images to Follmer/American Wheel Man, a book I published. Getting a chance to look at a significant amount of her work, I found attributes that are only found in the images of the best of that era. Her images are crisp, composed with a master’s eye, and always compelling. While we never really talked shop, per se, there’s a lot to be learned from the serious study of her work. She’s top-flight and a great person, too. I always enjoy reminiscing with Jutta, about our shared friendship of so many fellow photographers that are no longer with us. It makes me very happy to know that she is getting this well-deserved recognition.”

Her friends agree. On her 80th birthday recently, Bernie Ecclestone called to wish her all the best. So did Mario Andretti.

“I have known Jutta for 52 years,” said Andretti. “We met in Germany in 1969 at the Nürburgring. After that, I would see her everywhere. She was part of the global racing community and she would always greet me in pit lane or anywhere our paths crossed. She always had a smile and it was easy to develop a friendship with her. Her passion for motorsports was obvious and she was doing what she loved—and darn good at it. Even today when I look at old photos, I find myself thinking ‘That’s one of Jutta’s photos.’ I recognize her work and appreciate how good she was at capturing our sport. She is fondly remembered by many, many racers.”

“She’s just a very humble person,” said Pook. “A very, very low-key, humble person. I mean, some of these photojournalists have egos the size of the Eiffel Tower. And that’s not Jutta. Jutta’s very humble and very down to earth. And very… straightforward, uncomplicated.”

Which is why they’re still friends.

“You get to know the ones you want to get to know.”

At 80 years old she is retired and living in Costa Mesa, California, with her race-car-engineer husband John Ward, whose work you’ve seen in Indy cars and sports cars from Dan Gurney’s All American Racers, where he worked for decades. One wall of their house is lined with photos of John’s race cars, the other walls with all the photos Jutta took. It’s a heck of a house, so full of racing memories, winning car designs and the faces of friends who have come and gone many years ago. It’s not bittersweet, it’s a very warm and satisfying collection of great memories of a wonderful life.

Jutta Fausel-Ward lives in Costa Mesa with her husband, former racing engineer John Ward. Her work can be found at her website, www.fausel.photoshelter.com.

Source: Read Full Article